On September 1, 2018, I was ushered off the local college running track, which was closing for a field hockey match about to begin. As it happened, this abbreviated workout ended with the completion of my 3,000th mile of barefoot training, on the dot. I’d been working towards this goal with great enthusiasm since reporting on my 2,000th mile in December 2017 (and the first 1,000 miles the year before).

Why barefoot? In his bestseller, Born to Run, Chris McDougall argues that the more natural form associated with barefoot running reduces the risk of overuse injury, which is the bane of modern runners. I find this argument plausible, but there’s more to barefoot than just this. The practice calls to mind those free spirits who don’t readily submit to conventional wisdom, and it’s supposed to be simple, natural, fun. Recall Mark Twain’s young hero, Huckleberry Finn:

Huckleberry came and went, at his own free will. He slept on doorsteps in fine weather and in empty hogsheads in wet; he did not have to go to school or to church, or call any being master or obey anybody; he could go fishing or swimming when and where he chose, and stay as long as it suited him; nobody forbade him to fight; he could sit up as late as he pleased; he was always the first boy that went barefoot in the spring and the last to resume leather in the fall…..

Mark Twain, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Improving form and reducing the risk of injury was indeed the rationale for my barefoot training plan, but I’m also curious how much of Huck Finn’s youthful spirit is accessible to a person like me, that is a middle-aged man who’s worn shoes his whole life.

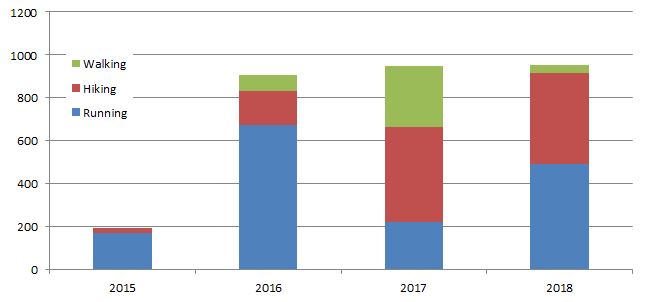

Summary 2015-2018

This journey started for me in May 2015 with a 1.5-mile barefoot jog around the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir in New York’s Central Park. This was an experiment to shed light on McDougall’s hypothesis on natural form and injury risk, and while there was no firm answer from this single run, the experience was intriguing. By the time 2015 was over, I’d run 194 miles without shoes, accounting for 7% of total mileage. Not every step was comfortable, but overall it was surprising was how much fun this was.

There were other motivations stirring in the back of my mind. For one, maybe it’d be smart for an aging athlete to do a little less. If speed and distance were limited by the sensitivity of my soles, that might reduce the load on muscles, tendons, ligaments and other body parts at risk of more serious injury. At the same time it would be exciting to have something to improve at, since it was becoming increasingly difficult (and would eventually be impossible) to beat the personal records I’d achieved in shoes. In 2016, barefoot training ramped to 904 miles, or 25% of total mileage.

With hindsight, however, trouble was brewing. As barefoot running expert Ken Bob Saxton points out, “barefoot running is so different from shod running that it’s practically a new sport.” He observes that beginners sometimes overemphasize the forefoot landing, which is understandable since without cushioned shoes, heel-striking is uncomfortable. But an exaggerated forefoot landing stresses the calf muscles. My training log from 2016 reads like a case study on this point. May 5, 2016: “left calf tightened up.” May 12, 2016: “left calf hurt.” May 15, 2016: “strained left calf again.” July 19, 2016: “pulled right calf muscle.” August 12, 2016: “strained left calf.”

At the same time that I was experimenting with barefoot form, I also pushed up total training volume significantly, with the goal of challenging a high profile ultra-distance record. Total volume in 2016 rose by 23% to 3,594 miles. But this volume, plus the barefoot transition, plus the effects of age, perhaps, was too much, or perhaps my luck just ran out. The record-breaking run never happened, while instead I succumbed to injuries, which sidelined me for the tail end of 2016 and most of 2017.

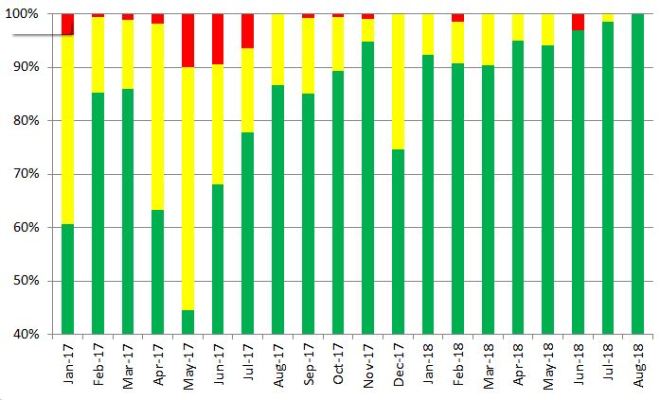

2017 was a very difficult year. Multiple injuries, some of which became chronic, forced me to develop new procedures. From now on, each walk, hike, or run would be coded in my training log as green (good), yellow (caution), or red (injury). When green dropped below 90%, as measured on a rolling 30-day basis, high-intensity activities would get curtailed. As a result, total mileage in 2017 was down 40%, and running volume was down more than 90%. In fact, I took seven months off from running to let a sore ankle tendon heal. Instead, I did a lot of barefoot hiking in the nearby Catskill Mountains, as this activity being slow-paced was easier on the body, as well as a lot of walking on treadmills or just around the block. Anything to keep moving without making injuries worse.

2018 has been so far a year of recovery. Having corrected the forefoot landing issue, my calves are feeling much better, and I continue to hike and run without shoes as much as possible (62% of total training volume year-to-date) because it’s more fun. In addition to continued hiking, I’ve gradually returned to running, reincorporated some high-intensity speedwork, and resumed racing, albeit at short distances. The emphasis has shifted from speed and distance, to a more balanced goal-setting process, careful assessment of risks, and strict focus on form.

Memorable Moments

- Hiking and running barefoot in snow (when conditions were within acceptable parameters).

- Barefoot hiking on New Zealand’s Kepler and Routeburn treks.

- Some slow barefoot trail running in the Catskills

- A 5k race on roads and trails

- A partial barefoot traverse of the Presidential Range in New Hampshire’s White Mountains.

- A trip out west that included barefoot hiking in Arches National Park, Canyonlands, Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park, the Grand Canyon, and Yosemite.

- Barefoot hiking in New York’s Adirondacks.

Lessons Learned

Over the last thousand miles, I’ve learned a lot about form, and not just from my own experience, but also from Ken Bob Saxton’s excellent book on barefoot running (which I wish I’d read earlier).

One of Ken Bob’s points is the importance of bending the knees, which he describes as “the absolute key to changing a collision to a gentle landing and probably in preventing running injuries.” Ken Bob describes his own running form as “somewhat squatted,” in a manner reminiscent of Groucho Marx’s trademark walk. This was something I began to understand while watching Alex Ramsey running at the Sri Chimnoy 10-day race in Queens. An accomplished barefoot runner, Alex was wearing sandals at this event, but even so his form was strikingly different from the other, conventionally-shod runners: Alex looked like he was running in a crouch, while the others seemed to be running stiff-legged.

Bending the knees is critical to running barefoot on rough surfaces, like gravel, but Ken Bob points out that you won’t necessarily learn to run this way on smooth surfaces, as I’d been doing. Once I grasped this point, I found a 1.5-mile loop in Central Park full of rocks and gravel, and began working on my form. My first attempts at this loop were extremely frustrating, taking me as long as 37 minutes, equivalent to a 2.4 MPH average pace — in other words, a few running steps here and there where the path was clear, and elsewhere picking my way along at a halting pace. With some practice, I’ve improved my time on this loop to 23 minutes, or 3.9 MPH, a mix of walking and jogging. It feels like there’s a lot of room to get better.

Keeping knees bent works the core muscles — so it’s not easy for those of us not used to it — but I’ve found that as my form has improved, I’ve experienced a special sense of lightfootedness, which is part of what makes barefoot running such an exhilarating experience. In fact, running in shoes is no longer appealing to me, because footgear makes me feel heavy-footed. It’s not the extra weight. Rather, in protecting the soles, shoes make that light step unnecessary, and the body naturally does whatever is easiest, which in my case means falling back into the habit of pounding the pavement.

For running on pavement, Ken Bob Saxton provides another important insight, noting how shoes make it easy to scuff or slide. Without shoes pavement may feel smooth initially, but if you scuff your feet — even by a tiny degree — the friction will eventually irritate the soles. After running in shoes for many years, I’d gotten in the habit of ever so slightly dragging my feet. This was made very clear to me in Utah, when trying to hike or run on slickrock sandstone. Yes, the rock surface felt “slick,” but it was actually of a similar consistency to smooth-grain sandpaper. After a few miles of tiny little scuffs, my soles started to hurt, just like they do after a few miles of pavement, and this forced me to pay more attention to the placement of each step.

In addition to physical form, barefoot teaches “mindfulness,” which is yoga-speak for the practice of paying attention. After an exhilarating trail run up and down Vly Mountain in the Catskills, I charged up Rusk and banged a toe. And then another and another. Ouch! Lesson learned: pay attention, or slow down. This was a frustrating experience, because I wanted to go faster, but in this regard an example of how the barefoot practice also teaches patience and humility, which for some of us are in short supply.

Why barefoot?

Sometimes when I encounter other hikers on the trail, they’re so surprised that I’m not wearing shoes, they look like they’ve seen a ghost.

“Where are your shoes?” they ask in bewilderment. “Please tell me you have shoes in your pack” a hiker begged me. Once a young fellow came running back, thinking I’d lost my shoes, to help me look for them.

There’s so much conventional wisdom about the importance of sturdy hiking boots etc. — what disturbs these people is that they’ve bought into this advice without ever questioning the assumptions. They’ve forgotten Huck Finn.

I want to tell them that there is indeed more in heaven and earth than is dreamed of in popular philosophies — but I keep my mouth shut, figuring we all need to be reminded of this point from time to time.

Onwards to 4,000.

Running the Long Path is available on Amazon (Click on the image to check it out)

[…] which incidentally marked my 4,000th mile of barefoot training. I reported previously on the 3,000th, 2,000th, and 1,000th miles, and this post is my latest update on what has turned out to be a […]

LikeLike