Arriving in Moab, Utah toward the end of July, car thermometer reading 100 F, windows down and a/c off (to help me acclimate), yellow sand and orange cliffs swimming in late afternoon haze. After a quick beer at a local brewery, it’s time to check in at the motel (the cheapest available), and begin planning the next day’s hikes at Arches National Park, located a couple of miles north of town and thus every tourist’s first destination.

A little after 7:30 AM the next morning, I’ve purchased my pass at the Arches National Park Visitor Center and am now strolling along a short trail called “Park Avenue,” enjoying the cool morning air, admiring the tall blocks of orange sandstone (reminiscent indeed of the Manhattan towerscape) and appreciating silky sand and smooth rock underfoot.

Next up is the 3-mile roundtrip hike to Delicate Arch, probably the most famous of the park’s 2,000+ documented arches (its image adorns the Utah license plate). Mid-morning now, the sun higher in the sky and getting stronger, the trail initially full of gravel but then the path climbs up a slickrock slope, and from a vantage point at the top there stands the famous arch, tall, stout, and symmetric. The tourists admire it from here, or some walk out to have their pictures taken underneath. In the distance, across thirty-five miles of desert, loom the 12,000-foot peaks of the La Sal Mountains, with a mass of clouds forming above.

When they see one of these arches, everyone wants to know, how were they created? (And so do I.) After reviewing various sources, this is the story I’ve pieced together:

The arches around Moab are generally formed of an orange sandstone referred to by geologists as the slickrock member of the Entrada Formation. Some 200 million years ago, Moab was part of a vast desert whose iron-rich sand (hence the orange color) was whipped by the prevailing winds into a sea of dunes. These dunes gradually hardened into a fine-grained sandstone which is slick to the touch (although grains of sand brush off the surface) and relatively strong.

About 65 million years ago, seismic activity resulted in some buckling of the crust in this area, and a long “anticline” or fold formed under the Moab region. This bulge was accentuated by the dynamics of a enormous layer of salt deposits (almost three miles thick in places), remnants of an ancient sea. Salt does not compress, so where accumulating rock layers push it down in one place, the salt gets squeezed upwards somewhere else, and this dynamic accentuated the anticline forming underneath Moab (geologists call it a “salt-cored anticline”). The resulting upwards pressure caused blocks of Entrada Sandstone to fracture into long thin walls or “fins.”

These walls are vulnerable to arch-producing erosion by water and ice because the Entrada sits on a weak, uneven, and crumbling layer of dark red-brown rock called the Dewey Bridge, which was formed from a mix of silt and mud deposited in tidal pools, and which was disturbed by earthquakes while still in the process of hardening. Water and ice work their way into the Dewey Bridge layer and underneath the Entrada blocks, undermining their structural integrity and causing large chunks to shear or spall off from the sides, forming ground-level cavities which over time develop into “windows” and then arches.

An arch is a robust structure for bearing weight, which is why we use them for doorways and domes, and perhaps arches in the Entrada Sandstone endure longer than the surrounding material. Of course, eventually the arch, too, collapses into rubble and sand.

After visiting Delicate Arch I call it a day, return to Moab, run a few miles around the local high school track to continue acclimatizing myself to the heat, and reward myself with an ice cream float.

The next day it’s back to Arches for a longer and more adventurous hike in a northern section of the park called Devil’s Garden. Once again the trail starts out covered in gravel but as it leads out into the desert the path turns to deep soft sand. I study some of the native inhabitants: sagebrush, blackbrush, yucca, mules ears, juniper trees full of blue berries with a scent reminiscent of gin (they are part of the recipe for London dry gin), and pinyon pine. A long-nosed leopard lizard pauses on the sand and then darts off.

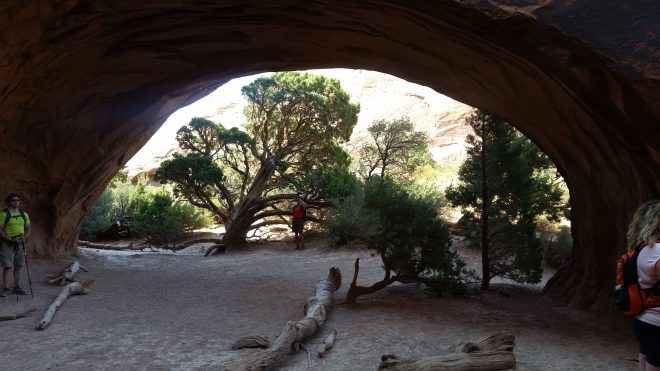

The trail leads past another arch, this one long and thin, with some material having collapsed recently from the underside of the span, and then heads up into a sandstone canyon. The slope gets too steep for my comfort, so I turn around and come back from the other direction (the trail’s a big loop), but the path takes me onto the top of a massive fin rising out of the desert sand, with a steep exposure on one side. The view is dramatic: you can see a number of fins stretching off into the distance and a deep canyon below. Uncomfortable with heights, I retreat once again, feeling somewhat humiliated to have been defeated by a trail across which a steady stream of tourists is marching nonchalantly.

Arches catch the eye, but then what? Such a simple form: tall or short, thick or thin, lengthy or narrow, it’s all the same basic shape. And always the same orange rock contrasting against the same blue sky, a contrast which the postcards and picture books photoshop to the maximum. The arch makes a great logo for the Utah license plate, but in so doing becomes a little bit of a cliche.

As a symbol, the arch has a long history. The Romans built triumphal arches to celebrate the return of a victorious army. In the Tarot card deck, the arch symbolizes renewal. In Lord of the Rings, an arched doorway opens into the underworld of Moria. In science fiction movies, an arch might be a portal to a different dimension.

I make a point to step through one of the arches in the park, wondering if I’ll be transported into an alternate world — and secretly hoping that it will be a world with less cliche and more natural wonder — but once on the other side, find myself still standing in soft orange sand, under the same blazing blue sky. Perhaps the arch is just an invitation. Perhaps when you pass through the arch you have taken but the first step in what will be a very long journey before you reach an alternate world.

And so it’s back down the sandy path and onto the gravel and to the car, thinking about other places to explore in and around Moab , wondering what else there is to see and experience in this strange desert region. . . .

Running the Long Path is available on Amazon (Click on the image to check it out)

Great post

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you 🙂

LikeLike

No problem check out my blog when you get the chance 🙂

LikeLike

Your words paint an amazing picture of a place I long to visit!

LikeLiked by 1 person

But did you go barefoot?

LikeLiked by 1 person

yes, those hikes were barefoot

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice work! I lived in the Central Australian desert and hiking barefoot in summer was a no go!

LikeLike

yes, the sand starts to get hot around noon…and as a result, I was doing 5-6 miles barefoot in the morning and then needing to put on shoes

LikeLike

[…] Reef National Park that resembles the U.S. Capitol Building, not to mention semi-circular caves and arches around Moab (later on an internet search will find 38 domes in the Sierras). And as for mass, […]

LikeLike

[…] Powell beneath cliffs of tan and orange, the Navajo and Entrada sandstone formations familiar from Moab. The desert keeps changing, and later on I’m driving past piles of brown and white […]

LikeLike

[…] trip out west that included barefoot hiking in Arches National Park, Canyonlands, Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park, the Grand Canyon, and […]

LikeLike

[…] One month later (it’s August now): it’s once again into the cumulonimbus zone, but this time the mid-afternoon sky is a peaceful shade of blue. These clouds may contain violent cells capable of producing lightning, hail, or even tornadoes, but for now they strike me as well-formed and graceful. One massive cloudbank contains a circular gap, reminiscent of the arches of Moab. […]

LikeLike