On May 27, 2019 I completed a slow-paced trail run in the Catskills, which incidentally marked my 4,000th mile of barefoot training. I reported previously on the 3,000th, 2,000th, and 1,000th miles, and this post is my latest update on what has turned out to be a fascinating journey.

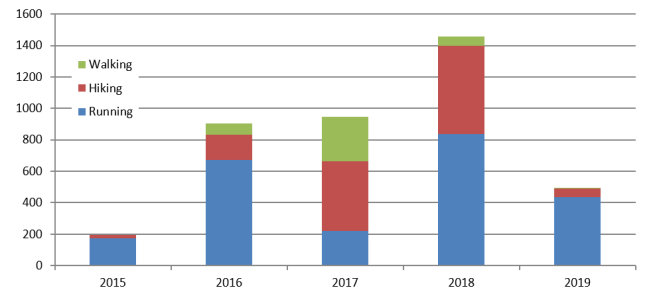

The story of the last thousand miles is a return to running, after a series of injuries in 2016-2017 that limited me mostly to hiking, and then a gradual recovery in 2018. But the main theme is getting better, and slightly faster, especially on rocky trails. And what fun it is to get better!

Miles 3,001-4,000 took place over the period September 2018 through June 2019. Mileage is down, but the mix has shifted back almost entirely to running because a new job hasn’t left much time to go hiking. Year-to-date, barefoot represents 81% of total training volume, with the remainder consisting mostly of training on the stairmaster and elliptical.

Barefoot Training Mileage 2015-2019

Since reaching the 3,000th mile in September 2018, I’ve completed several races barefoot: four 5ks, two 5-milers, and six 1/2 marathon runs, including the United Airlines NYC 1/2 and a relay leg for Rock The Ridge, which was my first trail race without shoes.

Getting Better, Getting Faster

Although I can run quickly on smooth surfaces, not surprisingly rough pavement or gravel slows me down considerably. Nonetheless, with practice, my times are getting a little quicker. For example, I finished this year’s Ellenville Run Like the Wind 5k in 26:30, an improvement from 29 minutes the year before (this year my pace varied from 7-minute miles on the smooth asphalt on the main street through town to 11-minute miles on some of the back streets where the pavement is rough and cracked). These times are nowhere near my personal 5k best of 18:12, but part of the motivation for barefoot was the thought that for an aging athlete, less speed and shorter distances might not be a bad idea (see discussion of injury risk below).

Another part of the motivation was the thought that even if my times were slow, I’d gradually get faster as I adapted to the new practice. Nowhere is this more evident than on challenging surfaces. At first rough pavement, grit, and gravel were so painful, I could barely walk on them. What I’ve learned from barefoot running guru Ken Bob Saxton is the importance of practicing on precisely these surfaces. There’s a technique to stepping lightly: you have to place and pick up the feet carefully, which necessitates engaging the core muscles and flexing the knees. Ken Bob calls it running in a “crouch.” A friend exclaimed, “it’s caveman running!” For those of us who’ve spent most of our lives sitting behind desks and traversing flat surfaces in cushioned shoes, barefoot running technique no longer comes naturally. In fact, it’s hard work, which is why the body will not adapt the technique unless you force it to.

Following Ken Bob’s advice, I picked out a rocky section of trail and have been practicing on it over the last year. The first time I tried to run this loop, it took me 36 minutes, which wasn’t even 3 miles per hour. If you’d been watching, you’d have seen me jog a few steps where the rocks weren’t too bad, then stagger across the gravel at a halting pace. More recently, I’ve cut that time in half. Although still quite difficult, it’s a remarkable feeling to move a little faster.

Injury Risk Management

The last 1,000 miles has also been a lesson in risk management, specifically with respect to injuries. In 2016-2017 I injured a tendon in the ankle (posterior tibialis), which eventually required six months off from running. After recovering in early 2018, I reinjured the ankle last fall by racing too hard in the last quarter-mile of the BMW Dallas 1/2 Marathon (someone was trying to pass me). Running guru and former Olympian Jeff Galloway warns that for aging athletes, excessive speed is the major cause of injury, and excessive ego is often the underlying problem, which sounds like an accurate diagnosis of my behavior. In hindsight, I went through a phase when I was so determined to improve my personal records, I literally ran myself to pieces. And not just me: I look at friends in their 40s, 50s, and 60s, and it seems like people are dropping like flies.

To manage injury risk, I’ve developed some new procedures. Back in 2017, I started coding runs in my training log as “green,” “yellow” (caution), or “red” (injury). As the following chart shows, 2017 was a difficult year with an enormous amount of time in caution and injured status, much of which related to the ankle, but other body parts were complaining, too. 2018 was a year of slow recovery, with another minor injury in June, and then the Dallas 1/2 marathon episode in December.

Upon reflection, I’ve embraced the need for a more careful attitude toward speed and distance, with the goal of never spending time again in the “yellow” status, to the extent possible. Following the late 2018 injury, I’ve implemented a second procedure, which involves tracking “irritation levels,” which means paying attention to aches and pains well before they become serious enough to limit performance. With respect to irritation status, “yellow” is defined as “aches or pains that are more than mild or transient” and red indicates yellow plus any noticeable level of soreness persisting afterwards. Some level of pain is inescapable, but when miles spent in yellow and red status are high, that’s a signal to back off, take a break from running, and go swimming or do weights instead. As the chart below shows, aches and pains from the Dallas 1/2 marathon injury in December have persisted for several months, but have been gradually improving as I’ve limited volume and speed.

These procedures force me to focus intently on how my body feels. Aches and pains are a good thing: they contain important signals. The other day I completed a very careful speed workout at the track: 7 x 1/2 mile splits, starting at a modest pace, and gradually accelerating, but the whole time the focus was on form, not pace. At a couple of points, I could feel my inner left calf tightening, which is indicative of stress to the ankle tendon, and at these points when I focused on proper alignment, the tightness eased. That’s how the feedback loop should operate.

Why barefoot?

Hearing that I’d run a trail race without shoes, a friend approached me the other day and mentioned that as a young child, she used to run barefoot around a nearby lake, pretending she was a deer — an attitude she attributed to being part Cherokee. She told me that she and her friends made a point to run barefoot on gravel, believing it was important to have tough feet.

In other words, the practice is about connection to nature and strength — something that kids understand and adults sometimes forget — what a great story!

I noticed that Running the Long Path has gotten a couple more reviews on Amazon and hope you have a chance to check it out. (Click on the image for more info)

Love the graphic analysis!

LikeLike

Delighted!

LikeLike

[…] I’d long been curious about this race because I wanted to experience the New Jersey Pine Barrens, and also because the trails were reputed to be smooth and sandy, which would be conducive to barefoot running. […]

LikeLike

[…] May I reported on reaching the 4,000th mile of barefoot hiking and running since starting the practice almost five years ago. Last week, the […]

LikeLike