When Born to Run was published in 2009, it caused a stir. To many people, McDougall’s thesis rang true – that running is a natural part of being human and so is going barefoot. More controversial was his claim that modern running shoes predispose us to chronic injury. The big heels, abundant cushion, and structural features designed to control the motion of the foot create a risk, McDougall argued – that they alter our natural gait. Why else would 70% or more of runners get injured every year, for participating in such a natural activity?

You could ask similar questions about other aspects of modern life. If eating is such a natural activity, then why are 74% of Americans overweight or obese?

Clearly, with technology we can solve for things like comfort and taste, since these attributes drive real-time feedback through sales. But that doesn’t mean we understand what drives health. Or the hidden costs and unintended consequences of having too much technology.

When Born to Run first came out, people saw barefoot running as primal. They understood intuitively that going barefoot offered connection and intensity, qualities which modern life sometimes lacks. The book was the catalyst for a boom in so-called minimalist footwear – lightweight running shoes with thin soles that let you feel the ground – sandals, like those worn by the Tarahumara Indians whom McDougall profiled in his book — or the funny-looking Vibram Five-Fingers with pockets for each toe. Some people unlaced their shoes and tried running on the unprotected soles of completely naked feet.

The enthusiasm faded quickly. People found the transition was too hard. Going from conventional to minimalist to barefoot exacted a toll on body parts that were used to having cushion. Many suffered injuries. For podiatrists, this was a windfall. Shoe companies profited by creating minimalist styles, and then they made even more money with by introducing new shoe types with even more technology.

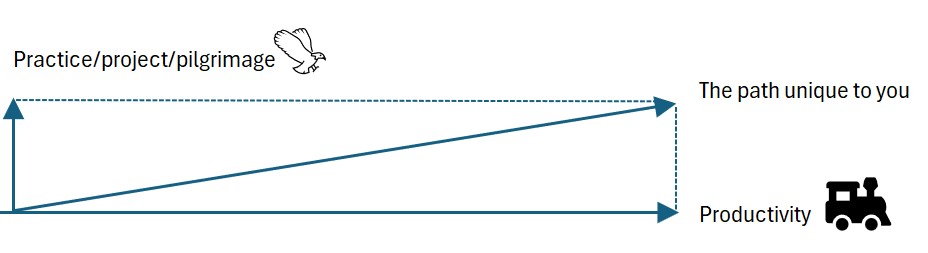

I, too, experimented with minimalist and barefoot running, thanks to Born to Run. I, too, suffered aches and pains and injuries and other setbacks. But my path must have been subtly different from those of other people, because I made the transition successfully and have not looked back.

My new book, Chasing the Grid, chronicles my pursuit of a peak-bagging challenge in New York’s Catskill Mountains, which I undertook both barefoot and in shoes. The book’s themes include the power of big goals to drive personal development, and how I adopted the philosophical principles of minimalism and transcendentalism as a consequence of spending time in nature. The story includes my first experiments with going barefoot, starting with the ascent of Peekamoose Mountain in September 2015, after which I was immediately hooked.

Benefits of Barefoot

What first impressed me about going barefoot was the intensity. The wild contrast between aggravating surfaces, like gravel and sharp rocks, and pleasurable ones, such as dirt, smooth slabs, and moss. In shoes, the difference is lost. Moving barefoot, I felt such a powerful connection to the land – as if I had become part of the forest, instead of merely passing through.

I soon recognized that there were physical benefits, too. Barefoot teaches you to step carefully, since you can’t afford to slip and stumble without shoes. As such the practice promotes agility and balance. As we age, slips and falls become an increasingly serious risk, indeed by the time we’re in our 50s, they are the number one cause of emergency room visits – which might well be another costly side-effect of wearing shoes.

When people see me barefoot, they often ask if I am “grounding.” There’s no question, in my experience, that going barefoot creates a sense of calm. Some people think this has to do with electrical forces passing through the soles. Maybe. I have a simpler theory – that there’s a lot of circuitry in the brain that’s evolved to guide us in motion, which includes directing soft feet on rough terrain. When these circuits are engaged, you experience the joy of moving naturally — call it “the original human mindfulness.” When the feet are covered and protected, this circuitry sits idle, making it easier for the brain to get distracted.

The biggest benefit of going barefoot is that it’s so much fun. Running without shoes is such a blast! I think McDougall is right – the practice has improved my form. I can run hard, go fast, cover long distances, and I feel comfortable and loose. You know how everyone talks about “pounding the pavement”? That’s not how you feel in bare feet. Instead, there’s an incredible feeling of light-footedness.

Suggested Approaches

Since that first climb up Peekamoose Mountain ten years ago, I have completed nearly 14,000 miles barefoot, according to my training log. These miles include 112 races completed barefoot, of which 23 were marathons and ultra’s (longest distance 50 miles). Plus a lot of barefoot hiking. I’ve thru-hiked the 211-mile John Muir Trial in California’s High Sierra and climbed 485 mountains barefoot, including many of the Catskill peaks as chronicled in Chasing the Grid, as well as Mt. Whitney (14,500 feet) and Mt. Elbert (14,440 feet), the two highest peaks in the Continental US. My training log includes hundreds of miles of barefoot walking, which is such a simple, easy way to take a break from hunching behind the laptop, get some air, enjoy a dose of natural motion, sustain the body – even if it’s a 1-mile stroll on the quiet country roads around my house, the sidewalk outside a hotel, or a treadmill.

So what did I do differently from other people who tried and gave up? And what would I suggest for those interested in exploring?

Start with barefoot walking

Most of the barefoot action in Chasing the Grid consists of walking along the trails in the Catskill Mountains or moving off-trail in the forest. In my experience, this is a much easier way to start, because walking doesn’t introduce the same kinds of stress as running, yet you immediately benefit from the sense of intensity, connection, and calmness, while improving your agility and balance. Let your feet guide you as to speed and distance, and carry shoes as back-up for when they’ve had enough.

By the way, you don’t have to start by climbing a mountain. Go walk barefoot in a local park. Take a stroll around town. If someone asks what you’re doing, tell them you’re experimenting with “grounding.”

Understand that barefoot is a slower journey

Whether walking or running, you’ll find that when the terrain gets rough, barefoot gets slow. When faced with sharp-edged rocks, gravel, and gnarly roots, you’ll have to look around before stepping and then place each foot with care. On rough trails, you shouldn’t expect to keep up with friends in shoes. On rocky trails, I’ve been overtaken by grand-parents.

Going barefoot requires patience, and I suspect this is the primary barrier to more widespread adoption. But don’t we have enough mindless rushing in our modern lives already? The American Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson advised people to “adopt the pace of nature – her secret is patience.” In my experience, barefoot is a great antidote to the state of constant distraction.

Start barefoot running on rough terrain

If you’re a runner and would like to give barefoot a try, make sure to start out slow and short. Your legs are strong, and you have plenty of cardio, but the barefoot gait is subtly different. You’ll need strong core engagement. Your joints, tendons, and ligaments will need to adapt to a slightly different geometry.

Instead of starting on a smooth surface like a track or a grassy field, the better approach is to find a trail with dirt and rocks. This will teach you the right form. You’ll learn to watch where you step. To place your feet with care and pick them up. You may find that you shift to landing on the forefoot instead of landing on the heel — although contrary to popular belief, you can run barefoot either way. You may find that you run in a bit of a crouch. A few years back, I picked out a 1-mile circuit on the bridal trail in New York’s Central Park. The first time out, the best I could do was walk — with a few trotting steps where the coast looked clear. After a year of practice, I could move across the rocks at an “easy” running pace. When rain left the soil soft and damp, I could hammer it at threshold pace.

Barefoot is More Fun

When people see me hiking on the trails or running in a race, they give me lots of positive feedback. They shout “respect” and “next level” and give me fist-bumps. They call me “warrior” and “badass.” The kids cry out, “look Mom, a barefoot runner!” Afterwards, people ask how long I’ve been running like this. They want to know, did I read Born to Run?

Barefooting is relatively uncommon, but there are a handful of us out there. Thea Gavin is a self-proclaimed barefoot running grandma and poet who’s completed numerous trail races without shoes. She’s also crossed the Grand Canyon barefoot. In one of her posts, she shared her favorite answer when people ask, why barefoot?

“Because it’s more fun.”

Which is what I now say. Sometimes I elaborate, explaining that “barefoot is for the experience, while shoes are for speed.”

In my opinion, Chris McDougall is right. We were born to run.

(Thank you, Chris.)

Chasing the Grid is available for pre-order on Amazon!