Notes on some of the other Catskills hikes that took place this month, with a special focus on views, birds, and battling the last remnants of snow and ice…

Uncategorized

Long Path Race Series: Announcing the 2017 Disciples of the Long Path

We are pleased to announce the winners of the 2017 Long Path Race Series! The Long Path is a 358-mile hiking trail that reaches from New York City to the outskirts of Albany, along the way traversing some of New York’s most beautiful parks and preserves, including the New Jersey Palisades, Harriman State Park, Schunemunk Mountain, the Shawangunks, the Catskills, the Schoharie Valley, and the Helderberg Escarpment. Created and maintained by the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference, the Long Path is a labor of love for some 250 volunteers.

Continue reading “Long Path Race Series: Announcing the 2017 Disciples of the Long Path”

Sights and Sounds of Winter

Henry David Thoreau, transcendentalist philosopher and author of Walden, wrote an essay on the colors of fall foliage. But what about the colors of winter? With this question in mind, I set the alarm for 5:30 AM and went to bed early. Tomorrow’s agenda would be to climb four of the Catskill high peaks with the goal of making progress toward the Catskill 3500 Club winter patch, as well as the Grid. And perhaps I’d see or learn something along the way that would help me better appreciate the winter mountain landscape.

Light and Ice in Minnewaska

John Burroughs once wrote that to be an observer is to “find what you are not looking for.” With this thought in mind, I set off for a trail run in Minnewaska State Park Preserve a couple of weekends ago, with no particular goal but to cover some ground and open my eyes. Perhaps I’d observe something that I wouldn’t have even thought of looking for.

Lichens

I’m reblogging this excellent post on lichens with great pictures and very helpful tips to identification

New Hampshire Garden Solutions

As flowers start to fade and leaves begin to fall my thoughts often turn to lichens, mosses and all of the other beautiful things you can still find in nature in the winter. We’ve had two or three days of drizzle; nothing drought busting but enough to perk up the lichens. Lichens like plenty of moisture, and when it doesn’t rain they will simply dry up and wait. Many change color and shape when they dry out and this can cause problems with identification, so serious lichen hunters wait until after a soaking rain to find them. This is when they show their true color and form. The pink fruiting bodies of the pink earth lichen in the above photo for example, might have been shriveled and pale before the rain.

Pink earth lichen (Dibaeis baeomyces) closely resembles bubblegum lichen (Icmadophila ericetorum.) One of the differences…

View original post 1,580 more words

Field Trip to Willowemoc Wild Forest

Hiking with Catskills forest authority Mike Kudish is a great way to learn to identify trees, shrubs, ferns, and mosses and understand the history of the forests. Last fall I accompanied Mike up the backside of Graham Mountain in his ongoing project to map the Catskills’ first growth forests, those regions that have never been disturbed by human activities like logging or farming. We met again recently, together with my wife, Sue, and Odie the Labradoodle, to explore the Willowemoc Wild Forest, once again with the mission of mapping first growth.

Losing Muir

I read a biography of John Muir, and his passion for nature inspired me to follow his footsteps into the mountains. But I hesitated. According to the bio, Muir believed that nature was love, goodness, an expression of God, and never evil, and he was often frustrated by his peers, whom he found materialistic, conformist, and indifferent to nature. But it seemed to me that logically, if humans are part of nature, then everything we do must be an expression of love and goodness, regardless of our attitude toward the wilderness.

Rocks and waters, etc., are words of God and so are men. We all flow from one fountain Soul. All are expressions of one Love.

— John Muir

Older, Faster…

“Of course you’re slowing down — you’re getting older,” the voice whispered, and I hated it. But it was true: this morning’s 1-mile repeats were disappointing, averaging around twenty seconds slower than earlier this year. “Age is catching up with you,” the voice continued, its tone at once insinuating and damning, “it’s getting harder to sustain speed.”

It’s not the fist time this voice has piped in; actually, I’ve heard it on and off for years. But when I looked at the data, I interpreted a different story.

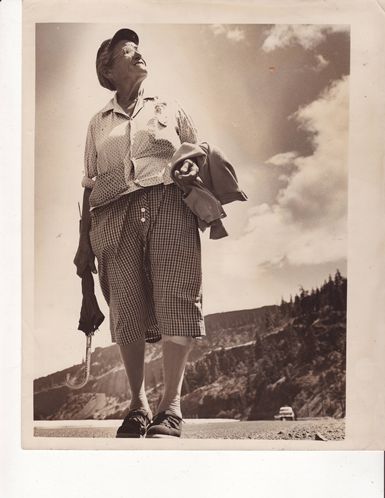

We Love You, Grandma Gatewood

I get faster as I get older

— Emma Gatewood

In 1955, Emma Gatewood (1887-1973) became the first woman to thru-hike the Appalachian Trail. She was 67. The AT was then 2,050 miles long, and she averaged 17 miles per day. By the end of the trip she had lost 24 pounds. Grandma Gatewood went solo, dressed in jeans and sneakers, and didn’t carry a tent, stove, or sleeping bag, but rather slung a sack with food and gear over one shoulder. She picked berries along the side of the trail and relied on the kindness of strangers. She’d sleep “anywhere I could lay my bones.”

The media called her “Queen of the Forest.” She came across to some as a “wild tramp.” According to one hiker who met her on the trail, “She was one tough old bird.” Grizzled Maine outdoorsmen lauded her for having “pioneer guts.” A Native American told her, “I’ve seen lots of things in the woods but you’re the most unusual sight I’ve ever come across.”

Two years later she thru-hiked the Appalachian Trail again. She completed it a third time in 1963 at the age of seventy-five. She also walked the 2,000-mile Oregon Trail, averaging 22 miles per day. For these accomplishments, she was described as a “living legend among hikers” and America’s “most celebrated pedestrian.”

She climbed mountains, crossed raging streams, endured rain and cold, slept outdoors, sidestepped snakes, killed and roasted a porcupine. All the while, “I kept putting one foot ahead of the other.”

In her eighties, she split her time between managing a trailer park, traveling the country as a celebrity, and blazing new trails in southeastern Ohio, where she lived. She received the Ohio State Conservation Award and the Governor’s Community Action Award for her “outstanding contributions to outdoor recreation.” After she died, a six-mile stretch of Ohio’s Buckeye trail was named the “Grandma Gatewood Trail.”

She thought people relied too much on cars and needed more exercise. “Most people today are pantywaist.”

Ben Montgomery tells her story in an interesting and well-researched new book, Grandma Gatewood’s Walk: The Inspiring Story of the Woman Who Saved the Appalachian Trail (Chicago Review Press, 2014)

The book opens with a description of her hardscrabble background, growing up on a family farm in southeastern Ohio, one of 15 siblings. She married and raised 11 children of her own. Her husband was abusive. She endured his beatings for twenty years before divorcing him in 1941 and obtaining custody of the children.

She had read about the AT in a discarded issue of National Geographic magazine and it had caught her imagination. But she didn’t tell anyone. In preparation, she made overnight expeditions in the local Ohio forests to test equipment, food, and first aid supplies. Her first trip to the Appalachian Trail ended in disaster: she started in Maine but quickly lost the trail and had to be rescued by park rangers. When she came back the next year, she started in Georgia and headed north. Maine was still a challenge, but she persisted despite bad weather, rough terrain, the loss of her glasses, which left her nearly blind, and a sore knee. Upon reaching the northern terminus of the AT on the summit of Mt. Katahdin, she sang “America the Beautiful.”

“I did it,” she said. “I said I’d do it and I’ve done it.”

People wanted to know why she undertook this challenge.

At first her answers were flippant: “I took it up as kind of a lark,” she said.

With time she provided more insight into her motivations. “After 20 years of hanging diapers and seeing my children grow up and go their own way, I decided to take a walk— one I always wanted to take.”

But why the Appalachian Trail?

“I’m a great lover of the outdoors,” she explained. “I want to see what’s on the other side of the hill, then what’s beyond that”.

“Some people think it’s crazy,” she told a reporter. “But I find a restfulness— something that satisfies my type of nature. The woods make me feel more contented.” Not only are the forests beautiful and quiet, but on the trail “the petty entanglements of life are brushed aside like cobwebs.”

Another reason: she wasn’t ready to slow down. “I don’t want to sit and rock. I want to do something.”

But why did she really want to do this? According to the author Ben Montgomery, the hike was a response to the abusive relationship she had so long endured, which included frequent and severe beatings. Montgomery speculates that her hike was a form of “walking away” from that experience as much as it was “walking towards” a specific goal.

Her daughter, Lucy, tells a different story. “Mama” was determined to do something notable.

One can speculate, but at the end of the day, the why may not matter. When one reporter asked why, she simply stated: “Because I wanted to.”

And that’s what’s so inspiring about her story: that she set out and accomplished her goal, no matter how improbable it seemed to others.

What did she think of the experience?

I thought it would be a nice lark. It wasn’t. There were terrible blowdowns, burnt-over areas that were never re-marked, gravel and sand washouts, weeds and brush to your neck, and most of the shelters were blown down, burned down, or so filthy I chose to sleep out of doors. This is no trail. This is a nightmare. For some fool reason they always lead you right up over the biggest rock to the top of the biggest mountain they can find. I’ve seen every fire station between here and Georgia. Why, an Indian would die laughing his head off if he saw those trails. I would never have started this trip if I had known how tough it was, but I couldn’t and wouldn’t quit.

These observations spurred local hiking clubs to improve maintenance of the trail. As her fame spread, more people began to thru-hike the AT.

Upon further reflection, however, she acknowledged, “After the hard life I have lived, this trail isn’t so bad.”

Despite all the challenges, or maybe because of them, it seems to me that Grandma Gatewood had a hoot on the trail. On her second thru-hike of the AT, she wrote to her daughters, “I am fine and having the time of my young life.”

I slept wherever I could pile down. Course, sometimes they weren’t the most desirable places in the world, but I always managed. A pile of leaves makes a fine bed, and if you’re tired enough, mountain tops, abandoned sheds, porches, and overturned boats can be tolerated. I even had a sleeping companion. A porcupine tried to curl up next to me one night while I slept on a cabin floor. I decided there wasn’t room for both of us.

On one of her hikes, she killed a porcupine, roasted it, and tried to eat it. She took a bite of the liver and immediately spat it out. “It took me two or three days to get that taste out of my mouth.”

A reporter asked her what part of the AT she liked the best. ‘Going downhill, Sonny,’ she replied.

She was audacious, unflappable, purposeful, practical, tireless, blunt, friendly, tough as grit, and public-spirited. And she had a sly sense of humor.

Emma Gatewood was inducted into the Appalachian Trail Hall of Fame in 2012.

Are All Things Numbers?

When you race you are under oath. You are testifying as to who you are.

— George Sheehan

I’m on the train to Boston for my third Boston Marathon. If I complete the full 26.2 mile distance, it will be my 16th marathon and my 61st race of marathon distance or longer. If I give credit to the longer distance covered in ultra-marathons (for example, a 100-mile race would be worth 3.8 marathons), then Boston will be, if successful, my 155th marathon-equivalent.

My goal is 2:57. If successful, this would be an improvement from 2:59:00 at NYC last fall and 2:58:48 at Boston a year ago. It would also be my 7th marathon PR and my 13th PR since turning 50.

These numbers don’t matter to anyone but me, but they do matter to me. They show who I am. Just like George Sheehan says.

I’ll put in a good effort at Boston, but the more I run, the less I fret about effort, and the more I think closing the gap between goals and reality. Numbers are important, because they help measure that gap. Otherwise, we get tempted to imagine closing that gap by creating delusional realities (“yeah, I could run 2:57 — if I wanted to”).

That’s why I like Archimedes, who is considered one of the greatest mathematicians of all time. He is credited with saying:

All things are numbers

— Archimedes

Heading into this race, I put especial attention on the taper. In the past, I’ve gained as much as 5 lbs. during the taper and recovery period (5-6 weeks of reduced training volume). Evidently it’s hard to change eating habits.

5 lbs may not seem like a lot, but imagine racing with a 5 lb dumbbell. It’d slow you down.

According to one study, a 5% increase in weight would slow a 150-lb runner by 30 seconds during a 5K. Extapolating from this, 5 extra lbs could cost me 3 minutes in a marathon, according to calculations based on the Jack Daniels pace calculator.

I don’t weigh myself every day and sometimes not for weeks, but three weeks before Boston, I stepped on the scale, and to my dismay, found my weight was 153.0 lbs, or 3 pounds above ideal race weight.

Then I strained a calf muscle, which required a week’s rest for recovery. Weekly mileage plummeted from 92 miles to zero.

It was easy to imagine showing up at the starting line with a 5 lb dumbbell worth of extra weight and a three-minute handicap.

To manage the taper, I began weighing myself daily and did a bit of swimming to keep up the training volume. Like most people, when I’m hungry, it’s hard to say “no,” but to the extent possible I tried to behave.

Seeing the numbers every day helped. It kept me focused on the goal. By Saturday morning, when it was time to hop on the train for Boston, I was down to 150.8 pounds.

Thank you Archimedes.

But I feel compelled to add a postscript.

When the Romans invaded Syracuse, they sent a Centurian to capture Archimedes unharmed. But the great mathematician was so involved in working through a mathematical proof, he refused to get up from his desk. The Centurian ran out of patience, and that was the end of Archimedes.

Are all things numbers? What do you think?