The goal was The Nine, a 20-mile loop in New York’s Catskill Mountains that connects nine of the highest peaks, with the special challenge that four of the mountains have no trail, meaning you must bushwhack through the woods using map, compass, and/or GPS. I had completed The Nine before during the summer, so you might assume I’d feel pretty confident. But now it was winter. And the prospects of navigating over rugged terrain, contending with treacherous footing, braving the cold — this was a little daunting.

NY NJ Trail Conference

Long Path Race Series: Announcing 2015 Disciples of the Long Brown Path

We are incredibly proud to announce the winners of the 2015 Long Path Race Series! We call these winners “Disciples of the Long Brown Path,” in a nod to the memorial plaque for Raymond Torrey, one of the Trail Conference’s founders and an early promoter of both the Appalachian Trail and the Long Path.

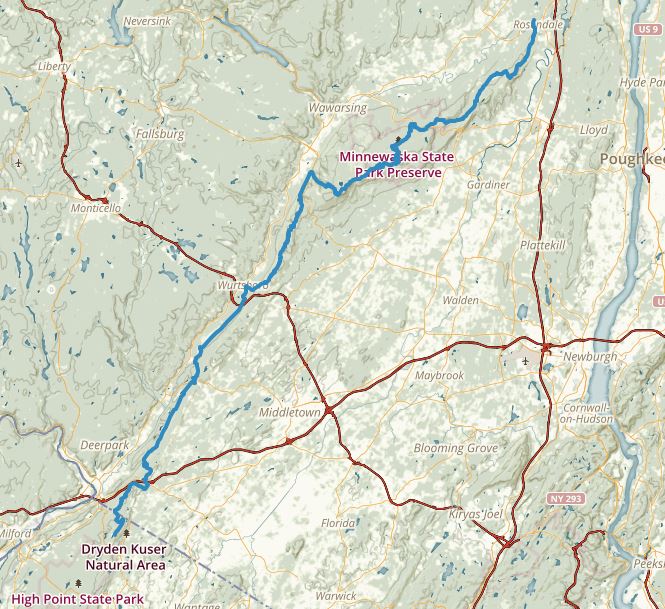

Created and maintained by the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference, the Long Path is an incredible 350-mile hiking trail that reaches from New York City to the outskirts of Albany, along the way traversing some of New York’s most beautiful natural parks and preserves, including the New Jersey Palisades, Harriman State Park, Schunemunk Mountain, the Shawangunk Mountains, the Catskills, and the Helderberg Escarpment.

Continue reading “Long Path Race Series: Announcing 2015 Disciples of the Long Brown Path”

SRT 2015 — Race Director’s Report

The 2nd edition of the SRT Run/Hike took place along the Shawangunk Ridge Trail (SRT) in New York’s Hudson Valley commencing Friday, September 18 at 6:35 PM and ending Saturday September 19, 2015 at 11:30 PM. The event attracted participants from New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Missouri, Connecticut, New Jersey, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Virginia, Washington, and California. 82 racers started out in four divisions ranging from 20 to 74 miles, ready to experience the beauty, ruggedness, and diversity of the Shawangunk Mountains. 73 made it to the finish line for an overall completion rate of 89%. A new record of 22 hours 2 minutes was set for the full 74-mile SRT. There were no reported injuries.

For the organizers, the event started many months ago. For 2015 we changed the format, increasing the number of divisions from three to four and holding them all on the same day. We also moved the last five miles of the course off paved roads and onto an unmaintained trail in the Mohonk Preserve. We spent the months leading up to the event obtaining six different permits, developing detailed safety plans, recruiting volunteers, and hoping people would sign up for an event that provides adventure but not support.

Ellenville Mountain Running Festival — Race Director’s Report

(Please note, the format for the 2017 event is different from the 2015 event as reported here)

What was remarkable: for all the challenges of racing through the mountains unsupported, there was a 95% completion rate. That speaks volumes about the runners’ skills and attitude.

Ellenville Mountain Running Festival was conceived as an event that would introduce runners to some of the most beautiful but less-used sections of Minnewaska State Park Preserve and Sam’s Point Preserve, which together comprise the largest preserved parcel in New York’s Shawangunk Mountains.

Continue reading “Ellenville Mountain Running Festival — Race Director’s Report”

Thru-running the Shawangunk Ridge Trail

Last weekend, I thru-ran the 74-mile Shawangunk Ridge Trail (SRT), establishing a new fastest known time (FKT) of 24 hours and 8 minutes. The previous FKT was 29 hours, which I ran in May 2014. Both of these FKTs are “unsupported,” meaning no aid from other persons or caching of supplies.

Thru-running the SRT is a special experience. The trail crosses a magical wilderness, and covering the distance all at once combines many impressions and feelings into a powerful appreciation for the land. By way of background, the distinctive white quartzite conglomerate which forms the Shawangunks eroded from the Taconic Mountains some 500 million years ago. 250 million years later, during the birth of the Appalachian Mountains, great plates of this conglomerate were tilted and uplifted, until the Shawangunks reared high above the Hudson Valley, dominating the landscape with rows of gleaming white cliffs, from which the vistas exceed 100 miles in some places.

That these mountains have been largely preserved from commercial development is no accident, but reflects the leadership of many people and organizations, including the Open Space Institute, which has acquired thousands of acres in the Gunks for parks and preserves, and the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference and its volunteers, who conceived of the SRT and maintain it and miles of other trails.

On Friday, July 3, 2015, my wife Sue kindly dropped me off at High Point State Park in New Jersey. It was a sparkling clear day. The plains of the Hudson Valley spread out to the east, while in the west the town of Port Jervis nestled in the confluence of the Neversink and Delaware Rivers. To the north, the Shawangunk Mountains reared like a series of breaking waves. My objective lay just beyond the last crest, some 74 miles distant.

Our dog Odie barked with excitement as I said goodbye and Sue wished me good luck. The southern terminus of the SRT was a quarter-mile walk away, at a junction with the granddaddy of american hiking trails, the Appalachian Trail. Just a few days earlier, ultra-running legend Scott Jurek had passed by here on a quest to set a new FKT for the 2,000-mile Appalachian Trail. My journey would be much shorter, my challenge, considerably less daunting.

My kit consisted of 1 liter of water, with a filter to resupply from streams, 3/4 pound of home-made pemmican, 3 dark chocolate bars, phone, lights, batteries, and an extra shirt. The pack weighed about 8 lbs. I carried trekking poles for the hills and wore lightweight minimalist trail running shoes (INOV-8 TrailRoc-235s). And perched proudly on my head was an embroidered Trail Conference baseball cap.

The time was 12:02. I noted this with pen and paper, at the same time pressing start buttons on GPS watch, satellite personal locator beacon, and smart phone map app.

For the first few miles, the rolling hills and southern hardwood forests of High Point State Park passed in a blur. It was a beautiful early summer day, pleasantly warm in the sun and cool in the woods. The trail meandered from narrow footpaths onto old logging roads and then darted back into the forest depths. I startled a bear, who bolted through the underbrush, disappearing in a flash of black fur.

After descending a steep slope, the SRT passed onto paved roads for a mile or two, at one point crossing beneath I-84. Above me, the holiday traffic had ground to a halt — the contrast between my freedom and the motionless vehicles seemed surreal.

Then it was up a hill, and I suddenly recognized Hathorn Rd. as a turn, but saw no blazes. Upon closer inspection, there were blazes painted on a telephone pole, but someone had nailed a sign on top of them. There was another blaze on a stop sign, but it was covered by ivy. Trail Conference volunteers do a magnificent job maintaining 2,100 miles of trails including the SRT, but they can’t be everywhere.

The SRT reentered the woods through a patch of mud, and shoes and socks were quickly soaked. The path turned to soft dirt then crossed a talus field of conglomerate boulders, forcing me to hop tentatively from rock to rock.

At mile 10, the trail paralleled an active railroad line, and then it jumped back into the woods, where I startled a second bear. A few miles later, I stopped by a rushing stream to filter fresh water. I drank as much as I could, hoping to minimize the number of stops.

And then it was back along the railroad line for another mile before the trail diverged onto an abandoned railbed. When I first ran down this trail in 2013, the chunky gravel had poked through the thin soles of my minimalist shoes, forcing me to detour into the woods to escape the painful pounding. But now, with more miles under foot, including some barefoot running, my feet didn’t seem to mind, at least not as much.

Experience and training pay off, and I was feeling good! Steady, strong, positive, now I was trotting purposefully under tall power lines, taking in the sun, the wind, the cries of of raptors wheeling in the air above, and even better, glancing at my watch, I saw mile 16 had clicked by in 4 hours, certainly a modest pace, but projecting out to the finish, this implied a sub-20 hour time — and a massive improvement over last year’s 29-hour run. Of course, the terrain would become significantly more difficult ahead, I knew this well. Nonetheless, a sub-20 hour time was the kind of wild goal that could help me push the pace while the course was still runnable, and I shifted into a more aggressive mindset.

Just past route 211, the SRT swings up to the top of a small hill called Gobblers Knob. In the past I had cursed the Trail Conference for this gratuitous climb, but this time I flew through the forest.

Bashakill is southern New York’s largest wetlands, a vast expanse of reeds filling a narrow valley; the trail hugs the shore, just inches above the waterline. I flushed mysterious-looking ducks who splashed away honking loudly, stepped over a turtle burrowing in the dirt, surprised a fawn which leaped away snorting. There was water on the trail, and my feet got wet, then dried out, then got wet again. Then I splashed into a section that was knee-deep. Looking up, I could see fully the next mile was under water, and I fumed about the delay as I slogged slowly forward. The trail emerged back onto dry land, and I finally escaped from the wetlands only to venture through an underpass beneath route 17 which was flooded a foot deep.

My water bottles were dry again. The town of Wurtsboro lay just ahead, and the idea of stopping in a bar occurred to me, but after careful deliberation, this strategy seemed questionable, although tempting. Reluctantly, I paused to filter some of the water that was once again streaming ankle-deep across the path.

The road through Wurtsboro allowed me to make up some time; police station, art studio, car repair, post office, motorcycle dealer flashed by, and soon I was climbing Wurtsboro Ridge and now for the first time encountering the difficult conglomerate jumble characteristic of the Gunks. I climbed up a rocky trail, then stepped carefully across slabs of conglomerate slanted at angles that could send your feet flying out from under you, and finally stopped for the first food of the day at mile 30, where I rested on a rock, watching the sun slip below the horizon.

The trail dipped into a deep valley, dark in the gathering dusk, then rose back up to the ridge, then it fell once again into the forest, and then it leaped across Ferguson Road and mounted the ridge once again. I was moving through the area of a recent fire, where the scrub oak had been burned away, allowing an aggressive colony of fern to claim temporary dominance. But other young plants were jostling for room and light; they appeared to be new shoots of blueberry, and I recalled that itinerant berry pickers used to set fires to improve the crop. Some of the pitch pine trees had been burnt from top to bottom and appeared lifeless crisps, but they had not given up the ghost: green shoots were emerging from charred branches and trunks.

My first break for food had consisted of a few handfuls of pemmican and a bar of dark chocolate, probably 1,000 calories of fat and not much else, and as much as I favor a high-fat diet, that was a lot take in at once. I felt a little queasy for the next few miles, and my pace slowed. A hint of smoke hung in the air. On the top of the ridge, a campfire was burning, the first sign of other people on the trail since the start, while way out to the west, fireworks dotted the horizon. I passed a trail marker and couldn’t find the next turn in the path. I circled around on the slope, fighting through burnt brush, and reemerged onto the trail covered in ash.

And then once again, the SRT dropped steeply off the ridgeline, taking me onto an abandoned road that the locals call “Old Plank.” Dance music drifted up, but deep in the forest, I couldn’t tell from where — I ran slowly along, enjoying the beat, remembered my goals, and sped up the pace, dodging the rocks and gravel that littered the washed-out surface and hopping over streams that had channeled through the road and were pouring into the depths below.

Old Plank reached route 52, and the SRT crossed this busy road and plunged into the woods on the far side, following South Gully up almost 2,000 feet to Sam’s Point Preserve. It’s the biggest climb along the SRT, but South Gully didn’t faze me now. Plenty of hill training over the last year had paid off, including running repeats on South Gully itself, as I had done with friends last fall.

From Sam’s Point, the lights of small towns and hamlets sparkled from the dark plains below. A rocky trail led to Verkeerderkill Falls, and once again I was teetering across sharply pointed blocks of conglomerate. Back in April, the snowmelt had flooded this trail, it had been a veritable stream, and now it was wet from recent rains, and soon enough, shoes were soaked. Up ahead the waterfall roared in the darkness, and I paused to filter more water before hopping across the channel, mindful of the 140-foot drop just a few feet somewhere to the right.

I moved past two sky lakes in quick succession. A layer of clouds had blocked the moon, and Mud Pond was not visible. Wooden boards took me across a marsh, sagging with each step. Then I scrambled up a small cliff, saw once again the lights spread out in the valley below, and passed by Lake Awosting in the darkness. The SRT descended through a field of boulders, worked its way through a squeeze behind an enormous block that had fractured and fallen onto its side, scrambled back up the cliff to Castle Point. Then it slipped down into a fold between parallel ridgelines, passing underneath Rainbow Falls. Water spattered down. Dawn broke. It was grey and drizzling. I was starting to struggle. The slanted rock faces threatened to send me flying, tangles of roots tired my feet, there were more boulders to clamber across. My breath was labored, energy was dropping, knees were aching. Even the slightest uphill slowed me to a walk, and scrambling up through clefts in the cliffs sent heart rate soaring.

I looked up from a vantage point: the rocky face of High Peters Kill beckoned in the distance, yet it seemed so far away. I felt drowsy. In 2014, I had stopped right here and laid down on a rock and closed my eyes for just a few minutes. Now my watch revealed a slowing pace. 20 hours was forgotten, 24 hours seemed unlikely.

Digging in with both poles at once, I levered myself forward, dragged my body to the top, made it to High Peters Kill, and surveyed the small bowl in the rocks with grim satisfaction, then tottered downhill past a luxurious growth of blueberries into the Mohonk Preserve, conscious that the remaining mileage was diminishing one step at a time.

Undivided Lot Trail clings to the side of the mountain high above the Coxing Kill, huge slopes looming across the valley, the Catskill Mountains floating somewhere off in the clouds. The path picked its way along the side of the mountain. I placed each foot carefully. But then the trail opened up, and I was running. The local covey of ravens took note, and its members called back and forth in loud, theatrical voices that reverberated among the trees. The path ended on another series of wooden planks through a marshy patch. Rain was falling steadily.

My breathing felt shallow and labored. I took deeper breaths, and this helped. My energy was low. I ate another square of chocolate, and this helped. My legs were no longer steady, but if I picked up my feet, I could still run, slowly, at least on the flats and downhills, and on the uphills I dug in with the poles and hauled.

From Crag Trail in the Mohonk Preserve, the SRT officially turns right onto Northeast Trail, but I turned left instead, taking a variant route designed to avoid paved roads (this will eventually become the official route). I passed the famous scramble up Bonticou Crag, and took instead a shorter climb to the top of this narrow ridge, glancing around at misty views of the surrounding hills and then quickly back at my feet. From the crag, a soft dirt road plummeted into a swamp with hemlocks and a rushing stream. The mud soaked through my shoes one last time, and then the trail followed a long spur down through lands recently acquired by the Mohonk Preserve, until it dropped me onto the rail trail. I ran across an enormous railroad trestle, 140 feet above the Rondout Creek, making sure not to look down.

I pushed the stop button on my watch and looked at my phone, estimating it would be at least 2:00 PM. But to my surprise, the time read 12:10 PM.

The SRT is an important trail, and it deserves an Olympic-caliber FKT. For now, 24:08 will have to do, but one day, a truly talented athlete, someone like Scott Jurek perhaps, will run the SRT in well under 20 hours. That might happen as soon as September, when we’ll hold a race along the SRT.

For me, it had been an amazing twenty-four hours, with several goals accomplished. An improved time. A reconnaissance of conditions to report to the Trail Conference. A training run to prepare for future endeavors. A new appreciation for a magical wilderness.

I wandered back across the trestle and found a little tavern in the town of Rosendale. An hour later, Sue and Odie arrived and very kindly brought me home.

The Day of the Bracken

In a previous post, I described the aftermath of a fire that scorched 2,000 acres in the southern Shawangunk Mountains. Just two weeks after the blaze, some friends and I ventured into the charred wasteland and discovered young ferns emerging from the blackened soil. I was fascinated by nature’s response to the fire and eager to return and observe further changes in the environment — and I was especially curious to see what the ferns would make of their early start.

Five weeks after the first visit, I ascended the ridgeline on the Shawangunk Ridge Trail where it is co-aligned with the Long Path, just north of Ferguson Road. Volunteers from the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference had been quick to put up new blazes, and the trail was as easy to follow as it had been before the fire.

Midway up the slope, I had not encountered a single fern, although other plants were now growing in the black soil. Where were the ferns?

While I pondered this question, I paused to admire the views. Spread out in the valley below was a small airstrip, and behind it lay the Bashakill, southern New York’s largest wetlands. Twenty-five miles distant, an almost microscopic needle could be seen rising atop the ridge: this is the memorial tower in New Jersey’s High Point State Park, where the Shawangunk Ridge Trail meets the Appalachian Trail.

In the foreground, the burnt stems of thousands of scrub oak bushes stood out in black, but the rest of the landscape was green. It was a warm, sunny day. A glider spiraled in the distance, and here on the ridge a pleasant breeze was blowing.

I walked another quarter mile and ascended another hundred feet up the ridge, and suddenly there they were: a sea of ferns flanking the path and stretching off in every direction. With the scrub oak burned to a crisp, sunlight now reached the ground, and the young ferns had unfurled their fronds to absorb the nourishing light. This was quite a change from before the fire, when the trail tunneled through dense thickets of scrub oak and blueberry, with ferns and other plants limited to the trail’s edge and other breaks in the brush.

But now the ferns were running rampant, a thicket of wild-looking plants, with broad triangular fronds thrusting aggressively in every direction. Upon close inspection, each frond was composed of multiple leafs, and each leaf had rows of small, weirdly-lobed leaflets.

Ferns once ruled the forests. During the Carbinoferous period (300-350 million years ago), the forests were dominated by giant fern trees and club moss, a fern relative, which today grows 3 or 4 inches on the forest floor, but back then soared 100 feet in the air.

Like other plants, ferns have vascular systems to transport water and nutrients from roots to leaves. But unlike flowering plants, ferns reproduce through spores, which lack the protective shells of seeds as well as the nourishment contained in the seed which helps the young plant become established.

Thanks to seeds, flowering plants have significantly outgrown the more primitive ferns, displacing them to marginal environments, like swamps or cliff faces or the dim light underneath the forest canopy. Firms adapted and survived, but they were no longer dominant.

After intensive research, I identified the fern spreading across the burned mountain as the common bracken (Pteridium aquilinum). It is an aggressive plant, reproducing not only through spores, but also by spreading vegetatively from underground roots (rhizomes) that can tunnel 10 feet deep. Given the opportunity, it forms dense thickets, and in some places there are enormous colonies which are thousands of years old. Bracken is also a wily competitor: it releases chemicals into the soil that impede the growth of other plants, and its dense foliage prevents smaller plants and seedlings from taking root. In some parts of the world, it has become a problem. For example, in Mexico, bracken has expanded considerably over the last fifteen years, exploiting human disturbances such as farming and ranching as well as hurricane blow-down. In Great Britain, bracken is thought to be a greater menace to biodiversity than foreign invasive species.

Scientists who have studied bracken describe it as a “postfire colonizer” which sprouts profusely from surviving rhizomes. Following fire, its new growth is more vigorous, and the fern becomes more fertile. In one study of Arizona pine communities affected by logging and fire, bracken fern grew to cover up to 30 percent of the area. A study in northeastern hardwood stands found that repeated fires could lead to bracken “domination.” After two successive wintertime prescribed burns in a Florida forest, the bracken was found to have doubled its biomass.

In the Shawangunks, a variety of ferns lurk in the forest shadows (hay-scented, Christmas, interrupted, and New York ferns are common), but I had never seen a colony of bracken expanding across the side of a mountain. I wondered whether the bracken would keep growing until it eventually engulfed the entire mountain range. It would be as if the Shawangunks had returned to the Carboniferous era.

But the bracken’s window to dominate is probably limited. The scrub oak (Quercus ilicifolia) is also known for aggressively responding to fire. Even if a bush is burned to a crisp, new shoots rapidly sprout from the stout taproot, as I could see happening all around me on the mountain. Indeed, not only is scrub oak an early colonizer of post-fire environments, it depends on frequent burning to flourish, because it cannot tolerate the shade of taller trees. This section of the Shawangunk Mountains is unique for the dense scrub oak cover, which indicates that it was likely clear cut or burned repeatedly prior to its acquisition by the Open Space Institute and designation as a state forest preserve in the 1980s.

For now, the ferns are running rampant, exploiting their day in the sun. No doubt the rhizomes are tunneling deeper into the soil and expanding the geographic reach of the colony. The bracken will flourish until the light is once again blocked by scrub oak and perhaps taller trees over time. Back in the shadows, the colony of ferns will bide its time, infinitely patient, waiting for the next fire, the next chance to expand, another shot at domination.