There are times to go fast and times to go slow. Recently I headed off for the Catskills with the goal of bagging a few more peaks for my record of barefoot ascents. It had rained earlier in the morning and was still cloudy, but the rain had let up, the winds had calmed, and the temperature hovered in the mid-50s — conditions which encourage a person to relax, move at a more leisurely pace, and take in the sights. In no particular hurry, I was sauntering up the gravel road that leads to the saddle between Bearpen and Vly mountains, looking down at the ground to avoid stepping on sharp rocks, when I noticed a small green ball of puff lying on the ground.

Nature

We may care about biodiversity, but does Nature?

I recently read The Future of Life by respected biologist, environmentalist, and Pulitzer prize-winning author Edward O. Wilson, who is not only the world’s foremost expert in myrmecology (study of ants) but also one of the most vocal crusaders for biodiversity. And he’s not just a scientist, he’s a great lover of nature. Early in the book he recounts one of the “most memorable events” of his life, when in 1994, in a back room of the Cincinnati Zoo, he encountered a four-year-old Sumatran rhinoceros named Emi. He gazed into her “lugubrious face,” placed a hand on her flank, and communed with the solitary animal, as he pondered the critically endangered status of her species.

His love for nature leads Wilson to issue a harsh indictment: “Humanity has so far played the role of planetary killer, concerned only with its own short-term survival,” he warns. “We have cut much of the heart out of biodiversity.” By this he means, we are responsible for a rise in the rate of extinctions and a decline in the remaining number of species. The causes are well known: hunting and poaching, loss of habitat, spread of invasive species, and now global warming. Wilson states that by 2030, the species count for plants and animals could be down by 20%, and if we freeze conservation efforts at current levels, he claims that 1/2 of plant and animal species could be gone by 2100.

An Armageddon is approaching at the beginning of the third millennium. But it is not the cosmic war and fiery collapse of mankind foretold in sacred scripture. It is the wreckage of the planet by an exuberantly plentiful and ingenious humanity.

— Edward O. Wilson, The Future of Life

After finishing the book, I reflected on this warning. I’m in favor of preserving wilderness, and I too would like to see the Sumatran rhinoceros flourishing again in the jungles of southeast Asia. But for Wilson, biodiversity means more than protecting Emi, it means maximizing the total worldwide species count. And here, his logic left me unpersuaded. There are better metrics for measuring biodiversity, it seems to me, and stronger arguments for conservation.

What I most appreciated about the book was Wilson’s emotional connection with nature, and on the very last page, I thought his comments were spot on….

Continue reading “We may care about biodiversity, but does Nature?”

Encountering Catskill Mosses

Last weekend, the weather was unseasonably warm for mid-March, with afternoon temperatures in the 60s. It was a great day to wander through the Catskills adding additional peaks to the list of completions. Rounding a bend on the trail between Balsam Lake and Graham mountains, I glanced to the right and spotted a marvelous moss tumbling down the side of an embankment, a cascade of silver feathery fronds.

Tree Pose

The Stoic philosopher and Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius once wrote,

It is in your power, whenever you choose, to retire into yourself. For nowhere either with more quiet or more freedom from trouble does a man retire than into his own soul

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

This advice reminds me of one of the messages in the Bhagavad Gita, a two-thousand year-old Hindu text:

Wherever the mind wanders, restless and diffuse in its search for satisfaction without, lead it within, train it to rest in the Self. Abiding joy comes to those who still the mind.

— Vishnu, Bhagavad Gita

I’ve been trying to put this advice into practice. Walking down the street in the face of an icy winter wind, I make an effort to relax. Instead of fretting at subway delays, I imagine shifting my brain into neutral gear.

The other day, arriving at a restaurant a few minutes before my wife, I took a deep breath and put away my phone…

Return to Point Lobos

I recently returned to Fort Ord for the first time in 30 years to participate in a trail race and arriving a day early, headed out for Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, which is located just south of Monterey along the northern California coast. It’s one of the most beautiful spots I’ve ever encountered.

Accepting the Universe

In his prime, John Burroughs (1837-1921) was one of the most popular writers in America, with a huge following of readers and relationships with the likes of Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and railroad tycoon E. F. Harriman. His passion was the birds, forests, rivers, and mountains of his native Catskills, and his writings reveal a scientist’s powers of observation and a nature-lover’s emotional connection to the land. In 1919, at age 82 he appeared in a short film, shown leading a trio of young children around his Catskill farm. He points out butterfly, chipmunk, grasshopper, and then the following words appear on the screen:

I am an old man now and have come to the summit of my years. But in my heart is the joy of youth for I have learned that the essentials of life are near at hand and happiness is his who but opens his eyes to the beauty which lies before him.

Today, these words are remembered by a dedicated group of Burroughs enthusiasts. But despite his enormous popularity, his hasn’t become a household name like other American naturalists such as Henry David Thoreau or John Muir. I wondered, why?

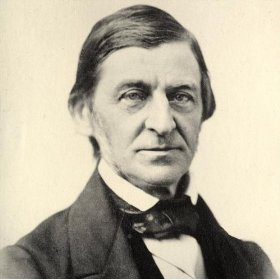

Transcending Emerson

When running in the mountains, I’ve seen many footprints on the paths. Sometimes I’m reminded of people like John Burroughs, John Muir, and Henry David Thoreau, who wandered the forests during the 19th and early 20th century, experiencing nature as a source of beauty, strength, and inspiration. There are older tracks, too, for behind these figures lurks another spirit: Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), the essayist, lecturer, poet, and father of the American Transcendentalist movement.

I hadn’t read Emerson since college, but one day it occurred to me that there could be a connection between “Transcendentalism” and the sport of ultra-running, if for no other reason that those who run longer distances than the conventional 26.2-mile marathon, are driven in part to do so by a desire to “transcend” perceived limits. I began to wonder, might ultra-runners be carrying Emerson’s banner, without even knowing it?

Running with the Wind

The weather station indicated a temperature of 39 F, intermittent rain, and gusty winds. Not a nice day in the conventional sense, but for those so inclined, a chance to get outdoors and mix it up with nature. In the back of my mind, I was thinking about the Yurok Indians of Northern California whose warriors would head out into the mountains during the stormy winter months to chase the Thunders, with the goal of demonstrating vigor and determination and, if they impressed the spirits, receiving special powers.

And so, I made my way to the paved trail that runs along the Chicago lakefront, but upon turning north, I found myself in for a rude surprise…

Losing Muir

I read a biography of John Muir, and his passion for nature inspired me to follow his footsteps into the mountains. But I hesitated. According to the bio, Muir believed that nature was love, goodness, an expression of God, and never evil, and he was often frustrated by his peers, whom he found materialistic, conformist, and indifferent to nature. But it seemed to me that logically, if humans are part of nature, then everything we do must be an expression of love and goodness, regardless of our attitude toward the wilderness.

Rocks and waters, etc., are words of God and so are men. We all flow from one fountain Soul. All are expressions of one Love.

— John Muir

Let’s Put Thoreau in his Proper Place

In a recent post, I compared a weekend spent hiking in the Catskills to Henry David Thoreau’s two-year sojourn at Walden Pond, as both were experiments in natural living and self-sufficiency.

But then my daughter Emeline brought to my attention a recent article entitled “Pond Scum.” The author, Kathryn Schulz, questions why we still admire the literature of a man who was mean-spirited and a fake. She summarizes her opinion in no uncertain terms: