“Put down the phone,” I bark to myself, and I know I need to. But I don’t. The device is engineered to be engaging, and the information is so intriguing – why, my social media feeds contain the latest headline news, and what my friends are doing and what they care about — which is all quite relevant to my life – and then an email arrives from a colleague with a new task awaiting my attention, a task which really matters. There’s the familiar ping – incoming text – it’s Mom with a report on what my daughter and grandson are up to. And I’m somewhat embarrassed to admit this, but I spend a lot of time on my phone doing word games, too. The dopamine hit from completing one puzzle always makes me want to start the next, and as a result I’m nearly 4,000 levels in. I do these games to help manage my stress and energy, in other words, to keep myself in the “flow.”

Indeed, I’m so absorbed, I often lose track of time. Is this not the very definition of “flow state,” the super-productive mindset that coaches, therapists, and scientists exhort us to attain?

Yes. But.

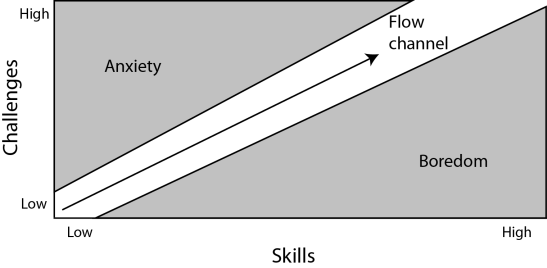

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the psychologist who coined the term, describes “flow state” as occurring when tasks lie within a narrow channel of difficulty that matches a person’s skills – not so hard as to provoke anxiety, not so easy as to bore you.[1] This is the so-called “flow channel.” But one shouldn’t jump to the conclusion that flow-state tasks are necessarily productive. Like, when after hours of scrolling, I awaken as if from a deep sleep, only to find I’ve made no progress on important tasks. Because these tasks are sometimes boring, and sometimes provoke anxiety. In other words, to get them done takes effort.

Speaking of which, it takes effort to disengage from the phone. I lift the device, extend my arm, and deposit it on the wooden corner table next to my chair. It feels similar to lifting a dumbbell in the gym, albeit the phone weighs hardly more than a feather, so the act of moving it burns probably less than a single Joule of energy (less than 1/1000 of a Calorie). But the mental effort is significant, for I must suppress that part of my mind which hungers for more information and dopamine.

So now, I’m lazing in my chair, glancing at the device out of the corner of one eye. From the table, it looks back at me, unreadable blank expression on shiny black face. It occurs to me that life consists of a long sequence of efforts, mostly small like this one, and occasionally some larger ones. Could effort be the principal attribute of life?

Which begs another question – if “making an effort” is so important, shouldn’t I close this laptop and drag myself to the gym or track to practice?

The Nature of Effort

Let’s put effort under the microscope. In the gym, we brace the muscles in the upper back and push upwards with triceps while contracting pecs and remembering to exhale – and presto, we’ve completed a repetition of the bench press.

While running we may not be conscious of specific contractions taking place in feet, calves, shins, quads, hamstrings, glutes. But we sense elevated heart rate and rapid breathing. In this case, effort is directed to suppressing mental signals which warn about depletion of energy and risk of strain, so that we can continue with the activity.

Effort can be broad and explosive – as in a jump. Or carefully metered with micro specificity – as in striking the cue ball in a game of pool at just the right angle and with just the right force.

What does effort look like? Picture a set of waves with different amplitudes and durations flickering on the screen of an oscilloscope. To be sure, the screen would show a complicated mix of frequencies, because there is effort associated with so many things: catalyzing physical motion, shifting and sustaining attention, calling information from memory, suppressing information we don’t want to deal with.

On an oscilloscope, effort looks like just another form of energy.

The body runs on energy – created from food, water, air – and the brain participates in this metabolic activity, consuming an estimated 20-30% of energy when the body is at rest, call it around 20 Calories per hour. But this energy powers mostly autonomous activity. It doesn’t take much (or any) conscious effort to breathe, or for your heart to pump. Voices in your brain chatter on endlessly day and night, as memories, dreams, and other subconscious calculations flash across your thoughts somewhat randomly and seemingly of their own accord.

A runner weighing 150 pounds burns something like 400,000 Joules of energy (100 Calories) in running a single mile, which produces roughly 150,000 Joules of mechanical work. In other words, running consumes a lot more physical energy than the muscular contractions needed to set aside a phone. But with respect to the energy used to act – maybe there’s not much difference. Scientists don’t understand much about how conscious effort gets activated in the circuitry of the brain, although they think decision-making activity take place in the prefrontal cortex, and they can measure depletion of blood glucose when people undertake tasks with significant cognitive load.[2] This means that cognitive processing consumes real resources. Effort is not free.

The Importance of Not Thinking

In his memoirs, the acclaimed Japanese novelist, Haruki Murakami, recounts how he completed a 62-mile ultramarathon, which was a significant physical and mental challenge for him, since it was more than twice the longest distance he’d ever run before. As he crosses the half-way point, things start to go wrong: his leg muscles tighten up, the pain becomes excruciating, he starts to feel like “a piece of beef being run, slowly, through a meat grinder.” To prevent the pain from overwhelming him, he repeats a simple mantra – “I’m not a human. I’m a piece of machinery. I don’t need to feel a thing. Just forge on ahead.” He describes the effort to keep moving as an example of “consciousness trying to deny consciousness.”

The mantra works. As he nears the end, he starts to feel the flow. There is no longer any need to “consciously think about not thinking.”[3]

Murakami was able to forge on by inhibiting the part of his mind that wanted him to stop. Which is similar to what I had to do in pushing the phone away – inhibit the part of my mind that wanted to stay engaged. Indeed, neuroscientists believe that inhibition is central to cognitive control. Although they do not understand much about how the mechanism works.[4]

Cognitive Control as Key to Flow

There’s nothing easy about achieving flow-state, according to flow psychologist Csikszentmihalyi. He warns you can’t learn flow from reading books — rather, it takes the fundamental ability to “give order” to your thoughts. Otherwise, the brain naturally descends into an entropic state of constant distraction. This raises an important question – can working out help you achieve a more ordered state of mind?

According to neuroscientists, the answer is yes. They find that more fit individuals are capable of allocating greater attentional resources to the environment and processing information more quickly, resulting in a better yield in task performance.[5] Physical exercise forces you deal with anxiety (can I do that last repetition of the bench press without straining my muscles or dropping the bar?). And with boredom, like when running on a treadmill. With practice, you improve your ability to suppress these negative emotions, which leads to an expansion of your flow channel. Now you can undertake a broader array of tasks while staying productive. Or take on bigger and more challenging tasks with potentially more valuable payoffs.

Striving to Still the Mind

The payoffs from cognitive control aren’t limited to productivity. Controlling the mind is foundational for how we achieve agency and personal sovereignty. Since homo sapiens is a social species, we internalize the opinions of other people. But sometimes it becomes necessary to suppress these voices, no different from how we inhibit the internal voices screaming at us to stop exercising.

In his classic, “Civilization and its Discontents,” Freud points out that people are inherently aggressive. As predators, aggression is part of our “intellectual endowment.” To preserve the peace, society deploys a host of mechanisms to restrain individuals from getting into fights, including obvious ones like laws and regulations, surveillance, and police enforcement. And more subtle methods, too, directed at getting people to internalize the rules, like religion, education, and propaganda. Freud coined the term super-ego to explain how social expectations can create a guilty conscience, whose duty it is to “torment the sinful ego” and thus prevent the individual from violating norms.

Writing nearly 100 years after Freud, cognitive psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman makes a similar point – “So many of us grow up being constantly swayed by the opinions and thoughts of others, driven by our own insecurities and fears of facing our actual self, that we introject the beliefs, needs, and values of others into the essence of our being. Not only do we lose touch with our real felt needs, but we also alienate ourselves from our best selves.”[6]

Not to mention, in today’s highly polarized world, the opinions and thoughts of other people often come in conflict. To make important decisions, you’ll surely have to suppress someone’s point of view.

Agency Creates Energy

To become our “best self” should produce a much bigger pay-off in terms of personal happiness than living in a state of self-alienation. A bigger pay-off, in turn, justifies a more substantial effort. This is basic cost-benefit analysis.

And there’s more. Because each time you complete a difficult task, your confidence increases. A greater ability to manage yourself through periods of anxiety and boredom implies a higher probability of success for all your goals. Applying higher probabilities to valuable payoffs justifies spending more energy. This, too, is basic cost-benefit analysis.

It’s like a virtuous circle. Practicing effort drives higher confidence and sense of agency, which in turn produce more energy across your entire set of tasks – including dragging yourself to the gym or track. Call it your personal flywheel.

Neuroscientists debate whether the sensation of relief which follows the completion of a run is caused by the release of endorphins or endocannabinoids. But that’s besides the point. “Runners’ high” is not about finishing one run – it’s about the joyful feeling of energy and self-empowerment which spreads across your life. This is how you feel when you’re confident about taking on important tasks. Because you know you can suppress the fear of anxiety and boredom and forge on. Even if you sometimes feel like a piece of meat being run, slowly, through a grinder.

Weight-lifters talk about “lifter’s high,” which presumably is similar to what runners feel (I do some weight-lifting, but with considerably less enthusiasm).[7]

So put down the phone.

You’re welcome to come join me at the track, even if you insist on wearing shoes.

[1] https://thelongbrownpath.com/2016/02/05/seeking-flow/

[2] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S030105110300156X

[3] https://newramblerreview.com/book-reviews/fiction-literature/running-out-of-thought

[4] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S030105110300156X

[5] https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3951958/

[6] In his book, “Transcendence: The New Science of Self-Actualization” See https://thelongbrownpath.com/2024/09/07/transcend-what/

[7] https://www.reddit.com/r/xxfitness/comments/mqv3f3/lifting_high_vs_runners_high/

Chasing the Grid is available on Amazon!