In recent years I’ve noticed that mental toughness has become a popular meme on social media. The topic reflects people’s aspirations for meaningful achievement. It draws energy, too, from concerns about our increasingly sedentary lifestyle. These concerns are not new. In his 1963 Sports Illustrated article, “The Soft American,” President John F. Kennedy reminded us of the link between physical fitness and moral courage. Warned of the deterioration in strength and health already apparent at that time (this was twenty years before the obesity epidemic took off, leaving us today with 74% of Americans overweight or obese). In 2016 Angela Duckworth argued in her bestseller, Grit, that our society needs more passion and perseverance. In 2018 ultra-athlete and former SEAL David Goggins published his memoirs, Can’t Hurt Me, rallying followers with his trademark exhortation — “stay hard.” Three years later, in the aptly-titled The Comfort Crisis, Michael Easter advocated for embracing pain as the key to happiness. Steve Magness’s new book, Win the Inside Game, which follows on the heels of his 2022 bestseller, Do Hard Things, offers specific mental strategies for toughness, drawn from his experience as an Olympic coach and performance scientist, which contrast with the traditional narrative of machismo.

My new book, Chasing the Grid, should serve as a useful case study for many of these themes. The story follows my adventures in the Catskill Mountains while working on a big peak-bagging project (it comprised over 400 separate ascents). In addition to the mileage and elevation gain, I had to overcome the challenges of terrain, weather, fatigue, injury, and age. The narrative showcases mental techniques that helped me execute against my goals. It also shares my mistakes and frustrations.

The topic of mental toughness is very personal. Since I was young, I’ve believed I had something to offer the world. But at the same time, I was conscious of shortcomings. I felt a strong imperative – to make myself a better person. And so began a journey which started as a teenage student of Shotokan Karate, participating in practices that entailed performing a hundred Kata or completing a thousand kicks or crouching in Horse Stance (knees bent) for 45 minutes straight. “Turn devil’s eyes on yourself,” our instructor Mr. Oshima cried out as our quads were trembling and burning – meaning that we should be relentlessly self-critical of our young selves and demand our best performance. The journey continued with a short post-college career in the US Army, where I trained as an Airborne Ranger, which involved going out on physically-demanding missions in the wild, at night, carrying heavy rucks, with limited food and sleep. The instructors were beyond demanding – for nothing mattered except measuring up to the task standards detailed in the Ranger Handbook and living up to the moral values of the Ranger Creed.

With the benefit of hindsight, I can look back at a 30-year career on Wall Street and in corporate America and state with conviction that nothing is easy. Everything requires mental toughness. And most of us need to keep practicing the relevant skillset throughout our useful lifespans.

For me, running was always first and foremost a practice of making myself a better person. Evidently that project has required a lot of work, for today my record stands at 110 races of marathon distance or longer, including ultramarathons and record-setting runs, like when I ran the 294-mile Badwater Double and set a new fastest known time (braving temperatures in Death Valley as high as 127 F). The philosopher of running, George Sheehan, used to say that every race was a chance to testify as to who you are. Today I can look back at every event I’ve completed (and some I did not finish) as a lesson in goal-setting and self-management. As an experience of energy, excitement, discomfort, pain, joy. As a source of confidence and self-empowerment. As a building block of my life. As an action that had a small but permanent impact on the world.

I’m pretty sure that the quality of mental toughness lies within everyone. As my coach Lisa Smith-Batchen used to say, “We have deep wells of strength.” It’s just a question of how that strength is accessed.

A Simple Framework for Mental Toughness

To understand mental toughness, we need to place the concept in the context of our life’s important work.

Borrowing from physics, let’s use the traditional definition of Work as equal to Force X Distance. For a runner, the idea is simple enough – we’re trying to move our bodies a certain Distance by getting ourselves from start to finish. Similarly, Force X Distance describes the farmer plowing his field or carrying crops to market, or any kind of physical labor. We can generalize the idea to mental labor, such as reading, writing, analyzing, coding, and the like. According to the field of information theory, we perform Work when we transform datasets into more ordered outcomes through the act of computation.

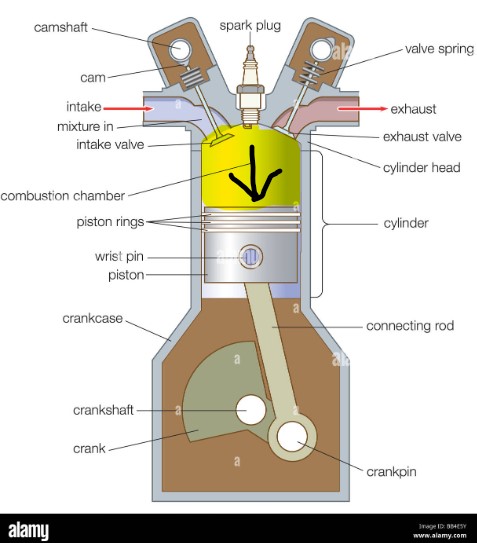

Work requires the application of Force, which is typically explained as a “vector,” consisting of a certain magnitude of energy channeled in a specified direction. Picture the cylinder in an old-fashioned gas-powered engine. Fuel and air are injected into the combustion chamber and ignited with a spark. The resulting explosion represents energy in its uncontrolled and undirected form, but the cylinder’s metal wall constrains the energy – forces it in one direction – the direction that moves the piston head downward, which turns the crankshaft and propels the vehicle forward.

Everything in life takes time and energy. Think of mental toughness as similar to the cylinder’s metal wall — the ability to control our mental energy and direct it to those mental tasks we must complete to achieve our goals.

Mental Energy Comes from Goals

Now you can be as tough as they come, but without energy, you will not get off the couch.

The abundant energy of life is evident in the tangled welter of vegetation in the forest and the proliferation of insects, birds, and animals into every conceivable niche. Like other animals we draw energy from sensations of pleasure and pain, but given our larger brains, much of our energy is filtered through our neural layers, with which we continuously form anticipations of pleasure and pain in future states. These anticipations coalesce into a set of goals which the brain is constantly updating – including such things as your next meal, a shelter from inclement weather, the spouse you’d like to find with whom to start a family, or the job you need to pay for that.

Runners understand that energy comes from goals. That’s why we sign up for so many races! We picture ourselves crossing the finish line and in so doing anticipate the joy and self-empowerment that comes from completing the event.

Now, for a goal to create energy, it’s got to have a reasonable chance of being realized. Otherwise, there’s no point. In the business world, we often pencil out expected payoffs using specific assumptions about dollar gains and the probabilities of success. For example, corporate sales teams might report out on client pipelines in terms of dollar revenues multiplied by subjective probabilities of winning the deal. Analysts might use statistical models to value financial assets as a function of projected cashflows in thousands of different scenarios. Runners make these same calculations, except we do so intuitively. Instead of thinking in dollar terms, we judge the importance of outcomes by the emotions stirring in our hearts. We estimate the odds by listening to our fears, which sometimes manifest in the form of cautious voices inside our heads.

The 19th-century American Transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that “Life is an ecstasy. Man is a jet of flame.” That’s how you feel when you move through life with meaningful, achievable goals. Goals with so much energy you feel like a race car driver flying along the track. Or a fighter pilot maneuvering at low-altitude. That’s how I felt during my ultra-running days, when I moved from one race to the next with wild exhilaration.

Everyone is tough, in my opinion. But not everyone has identified meaningful goals. Steve Magness advises elite athletes to spend more time “exploring,” before they narrow their focus onto the next set of performance targets. Maybe, he writes, you should organize your life around a “quest.”

Our Brains are Continuously Updating Probabilities

It would be nice if the world were simple and life predictable — instead we bob and rock in a sea of uncertainty. What seemed this morning like an exciting payoff with a high probability of success may feel infeasible in the afternoon when you look out the window at lashing rain. The next day the sun is shining, and now anything seems possible. A shifting outlook can be aggravating, because our brains are constantly updating probabilities. As a result, we may experience swings in mental energy, as hope and pessimism oscillate like sun and clouds on a windy day. The philosophers of ancient Greece labeled these mood swings as “perturbations of the soul.” Today we use words like “stress” and “anxiety.”

In Chasing the Grid, I set after a goal which seemed almost in reach – only to be stymied by steep, rugged terrain. Dense fir-spruce thickets which were nearly impassable. Vegetation so thick I couldn’t see a thing. Then I got injured. In due course winter arrived, and with sinking heart I realized I had nearly 100 climbs to do in desperate conditions, with snow so deep and heavy that even in snowshoes it sometimes took two hours to go a mile. The runner in me was screaming in frustration.

What I learned to do long ago during my Wall Street career – and what I apparently had to learn again during my adventures in the Catskills – was to react quickly to new challenges. Acknowledge the problem. Diagnose the root cause. Revise plans accordingly. Come up with new timelines. Different routes. A whole new set of goals. I call this “recasting.” In the field of business strategy, it’s sometimes called “pivoting.”

Suppose while training for an important race you experience a worrisome new ache (what runners call a “niggle”). Should you run through it? Or would it be better to take a break? This is a high-stakes situation, since the wrong decision could imperil your training plan and dash your hopes for a strong performance at the race. There’s no way to know for sure what the niggle portends – yet you could spend a lot of time fretting. Instead of succumbing to anxiety, how about making a quick decision – for example, do another run but keep it short and easy and see how you feel.

It’s good to “recast” your goals in a speedy manner, because anxiety drains a lot of energy. If someone has that look of mental toughness, it doesn’t mean they don’t have problems –maybe they were quick to recast their plans and now they’re back on track racing toward a revised set of targets.

Managing Cognitive Load

We have many problems to solve in life, but limited time and energy. Especially when operating in a high-stress environment. So let’s talk about how to manage your mental resources.

Mental force requires making an exertion. A concerted effort to focus our attention on what matters and overcome the sensation of discomfort. In shorter races, we focus on pace and form and turnover and on swinging arms, while muscles ache and lungs are burning. If you’re on the trails, you might have to contend with steep climbs — slippery descents — uneven footing, all of which requires care. For longer events, more variables come into play – nutrition and hydration and gear and clothing for different weather conditions and suppose the course is unmarked, meaning you are responsible for navigation – and now the sun is sinking and darkness falls. At the same time that all this is going on, your brain is updating the probability of success, or at least trying to. Sometimes the inner voices get nervous. Can I really make it to the finish line before the cut-off? Should I keep moving through this pain — or will I sustain an injury?

This is an example of complex problem-solving in a high-stress environment. There’s so much discomfort. Pain. Fear. The probabilities of success are no longer clear – you may be experiencing wild swings in energy as early optimism crumbles in the face of reality. The voices grow insistent. You lose control of the inner dialogue. Welcome to those “perturbations of the soul” the ancient Greeks warned of. It’s like the cylinder in your gas engine has overheated and warped or cracked. Power plummets.

In situations like this, people quit. Which is understandable. Although disappointing to the extent they could’ve kept going. Quitting doesn’t mean they’re mentally weak. They were overwhelmed by excessive cognitive load.

You can drive a race car really fast around the track, but be careful not to redline the RPMs, lest you put the engine at risk. To help you manage your mental RPMs, here are some techniques (explained at greater length in Chasing the Grid):

Use Training to Strengthen Your Mind

Weightlifters build muscle by “training to failure,” and the same principle applies to the mind — you can improve your ability to operate under stress by incorporating a variety of stressors into your training. For example, runners can train for longer distances or work on speed, carry more weight, train at higher altitude, expose themselves to heat and cold, or go without food, water, and sleep. At a minimum, by building familiarity with how these stressors feel, you’ll develop an appropriate level of self-confidence.

By the way, the ancients Greeks used the term “askeisis” to denote rigorous training modalities designed to promote both athletic and spiritual development, and JFK had this practice in mind when writing about physical fitness back in 1963. He thought it would take moral courage to stand up to the Soviets and that physical strength would help citizens and their leaders make the right decisions under stress.

Reduce Cognitive Load by Planning

Too much uncertainty is hard for anyone to deal with. To avoid getting overwhelmed, consider rehearsing how you will react to various contingencies. For example, a runner could develop a pace plan based on the nature of the route. — memorize the course — check the weather forecast and possible extremes — lay out and test their gear.

In US Army Ranger School, we were taught the 5 P’s – “Prior Planning Prevents Poor Performance.” Every training mission was preceded by a planning session, which included a detailed operations order specifying the mission’s objectives, a sand table version of the map so that everyone could grasp the lay of the land, inspections, radio checks, rehearsals of close action drills. This preparation was essential to managing complex operations in the field which were difficult enough in peacetime, without live ammunition going off in both directions.

Practice Self-discipline

Mental energy may manifest as enthusiasm and sweep you along towards your goal – but sometimes it’s necessary to stop and fix things, which is where discipline comes in. You must direct a portion of that seemingly boundless energy towards a set of unglamorous tasks. Think procedures and checklists designed to keep you on plan. Like stopping to eat before you “bonk.” Drinking before you’re dehydrated. Taping up a hot spot before it turns into a blister. Stopping to check the map before you wander off course. Fixing that shoelace before you trip.

In another example of managing cognitive load, there’s a saying among fighter pilots, when operating in a low altitude regime — “climb to cope.” You can’t divert attention to some problem when the distance between everything being good and disaster is measured in split seconds. Climb to a safer altitude where you have time to think through whatever needs to be fixed.

Make an Effort to Relax

In his memoirs, acclaimed novelist Haruki Murakami describes running as an exercise in “not thinking.” He writes about not seeing and not feeling and the odd trick of “consciousness trying to deny consciousness.” The fact is, so many of our problems are “intractable,” meaning unsolvable even if you had unlimited time and energy. Like that “niggle” – there is no way to know for sure whether it is a minor annoyance or the start of a serious injury. If you let your mind keep churning over these kinds of problems, you’re not really solving anything. You’re just wasting energy. Even worse when the mind becomes anxious about its own anxiety.

In the Indian religious text Bhagavad Gita, Lord Krishna counsels the warrior Arjun – “abiding joy comes to those who learn to still the mind.” If this does not come easily, he adds, you may need to strive to still the mind. It’s ironic, but sometimes you must make a concerted effort to relax. Possibly that’s one of the most important skills you’ll develop during training.

Chasing the Grid is my story of taking on big goals in New York’s Catskill Mountains. It’s got a mix of frustration and success – plenty of rapid pivots – and examples of moving in high-stress regimes. The experience turned me into a different kind of runner and possibly a slightly better person. If you happen to do some exploring in the Catskills, you might see me on the trails. My journey is not yet over. I am still trying to improve.