When I first heard of the Barefoot Autism Challenge, I immediately thought of art museums. Not that I am a fan. They make me feel claustrophobic. When I do visit one, I rationalize that there’s only so much I can absorb. So I fly through the place, taking in a handful of paintings and a few sculptures, but all the while, I sense the ticking clock.

Why did the Barefoot Autism Challenge spark the thought of art museums? Maybe when you take on a challenge, it shakes up your thinking. Lets loose some new ideas. Arguably that’s the point of taking on any kind of challenge. In any case, I do remember the first time I ran the Ft. Worth Cowtown Marathon, how right by the starting line there sat a low concrete building with a plaza and a forlorn sculpture. After the race, as I walking back to the car, I looked up and saw the place again. Stared for a moment. Wondered if they’d let me in without shoes (Cowtown was my first barefoot marathon). Maybe that’s where the idea came from.

The Challenge is simple — go somewhere barefoot for the experience and to show support for the autistic community, where barefooting is popular for the sensory input which helps with processing information about the environment. I decided to give it a try at that museum by the Cowtown starting line.

Recognizing that barefoot is an unusual mode of dress, I went out of my way to make a good impression. I dressed up in stylish jeans and an expensive fitted shirt (the kind I used to wear during my banking days). Traded my Yankees cap for one with the logo of the Dallas Cowboys (the better to fit in with the local crowd). Rehearsed answers to all the questions I thought might be asked. And then, on the appointed day, freshly-showered and cleanly-shaved, I strode in confidently through the front door. And was immediately intercepted. And shown right back out.

I demanded to see the manager. A few minutes later, a portly gentlemen emerged wearing a navy blazer. He was courteous and patient. Explained, “It’s the law.” Talked safety, too — when they move the art around, small tacks might fall out from the frames.

I could think of nothing to say in response to such nonsense.

On the way back to my car, a woman observed how lovely Texas weather was, that you could go about barefoot in November. This comment made me smile. But, I am a stubborn man. I vowed I would return.

Tampa

Fast forward to February — I’d arranged a short visit to Tampa to get some sun and a break from New York winter.

It had taken multiple emails and phone calls, and two of the three institutions I approached said “no,” but when I strode into the Tampa Museum of Art, the woman behind the counter shook my hand. Denise Esquibel-Rangel, Visitor Experience Team Manager, had approved my visit and was here to personally take me on a tour. I followed Denise through the galleries. Listened to her explain how the museum sought to engage with its diverse community. Saw a wild mix of colors and textures. Never even thought about my feet, except for the sensation of smooth surfaces.

Thanks to Denise, a precedent was set.

As an aside, the Tampa visit was also an opportunity to run another marathon, which went well enough, except I didn’t drink any water until mile 22, which turned out to be an ill-advised hydration strategy considering strong Florida sun and exposed course. Cramps notwithstanding, I finished. The next day, for recovery, I strolled along the nearby Clearwater beach. Enjoyed the clean, white sand. Drank in the brassy colors of the setting sun. Ate dinner in a beachside crab shack, without shoes.

Dallas-Ft. Worth

And then it was back to the Dallas-Ft. Worth metroplex, which I visit frequently since my employer is headquartered there.

Once again, it took a concerted, organized, and persistent campaign, and at first there was no response. Until I managed to get through to Ken Bennett, who heads up security. He sounded sympathetic to the idea and referred me to Melissa Brito, Manager of Access Programs and Resources, who graciously approved my request to visit the Dallas Museum of Art without shoes.

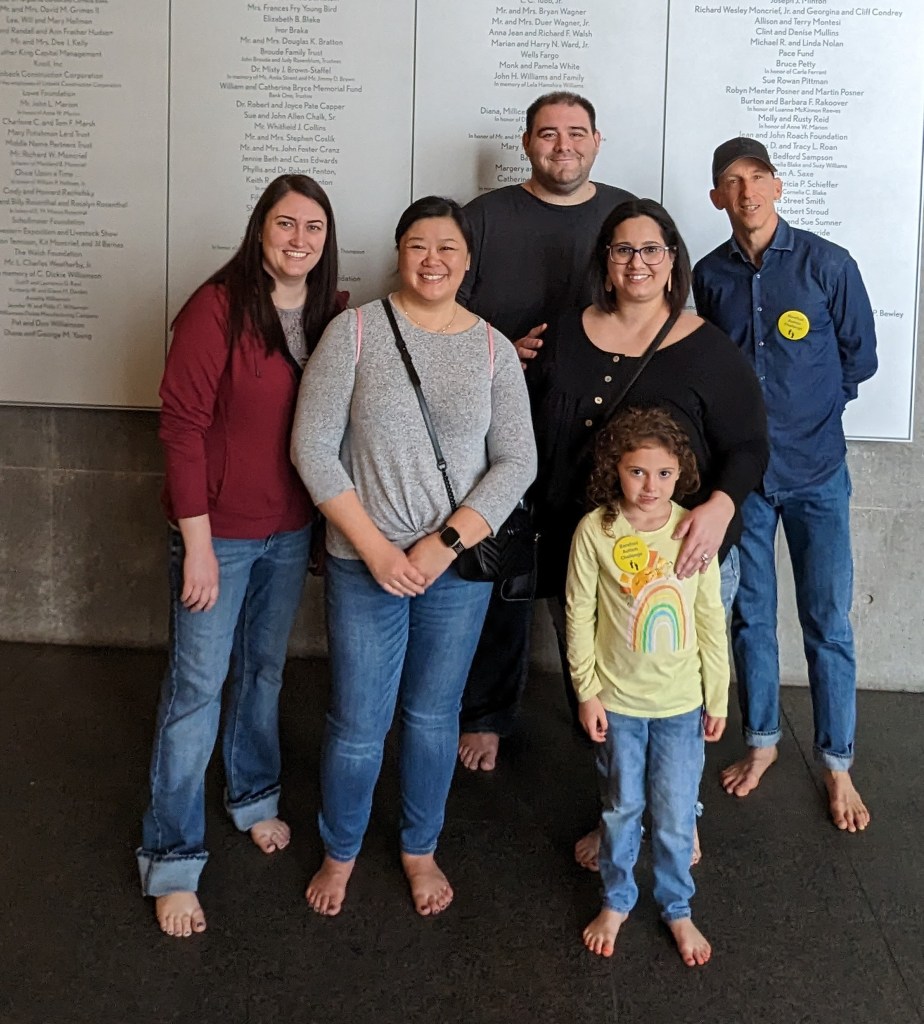

On this visit I was joined by Elizabeth, a former colleague and fellow runner, and her daughter Riley. As we strolled around, I asked Riley what about a barefoot museum visit had appealed to her, and she replied that when she was young, she enjoyed walking barefoot around town. Until one day, some adult told her not to. Evidently, in this world there is no shortage of scolds. Sometimes the barefoot practice triggers an attitude of intolerance, possibly because barefoot is associated with and free spirits.

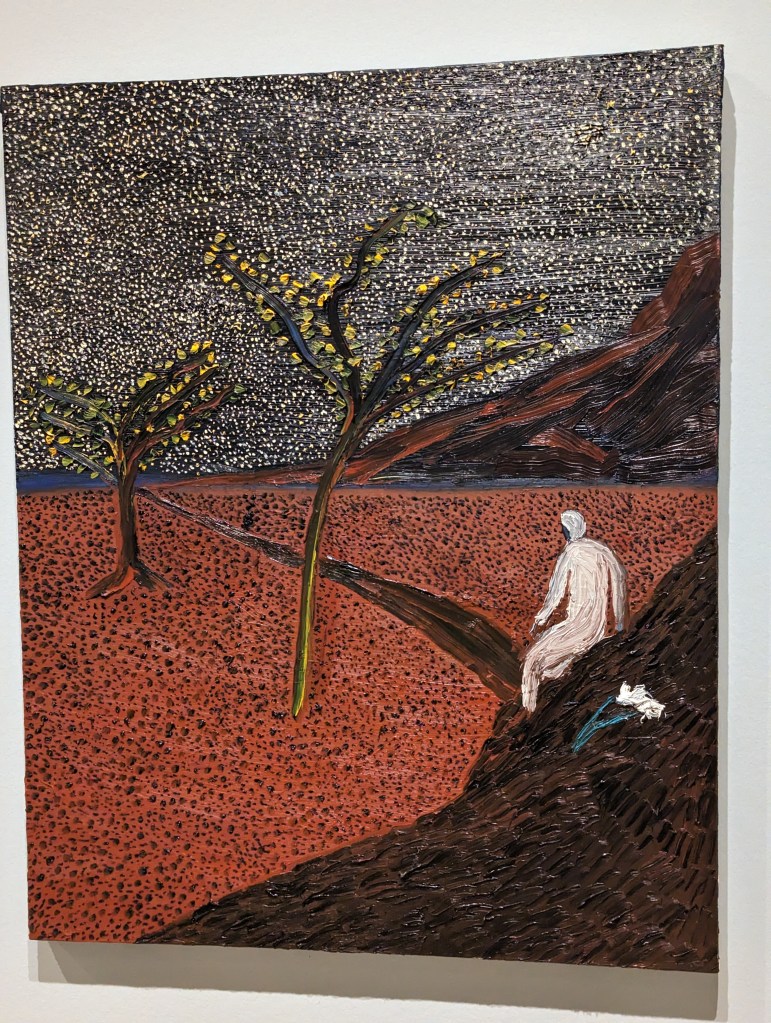

Among the collections we visited, I especially enjoyed Edward Wong’s paintings. There was a twilight scene with a pathway snaking through the woods, the blue tints evoking a feeling of melancholy for the passing of the day and a sense of mystery in the darkness rolling in. Solitaire (2016) shows a lone figure lost in a wild mountaintop scene, which I instantly recognized as the vista from Mulholland Drive overlooking Los Angeles. Even though it must have been twenty years since I was there. The painting also reminded me of the passage in Thomas Pynchon’s Crying of Lot 49 where the story’s protagonist looks down a slope, squinting in the sunlight, onto a vast housing complex — and thinks of how she once opened a transistor radio and for the first time saw a printed circuit board.

“The ordered swirl of houses and streets, from this high angle, sprang at her now with the same unexpected, astonishing clarity as the circuit card had. Though she knew even less about radios than about Southern Californians, there were to both outward patterns a hieroglyphic sense of concealed meaning, of an intent to communicate.”

The Crying of Lot 49

Later that afternoon at the Ft. Worth Modern, I was striding around a pile of electronic parts scattered on the floor (someone must have dashed a computer to pieces — but hey, it’s modern art), in pursuit of Marie as she scampered into the next room, where I could sense the glow before I even saw it — and by the way, nothing could be more natural than a 5-year old running barefoot through marble halls, pausing from time to time to stare and point, as the four adults in our party strolled along behind her. The glow came from a large panel aflame in reds and yellows, composed of 1,152 small images, each of them a sunset photo scraped from social media. The warm colors were energizing. But when I squinted at one of the individual sunsets, the image was a blur. Suddenly the impression felt artificial. As if a diluted experience had been repackaged. I wanted the real thing.

The Dallas sky obliged, the very next day, as I was driving to a business dinner. At first it was just a hint, behind a row of tangled post oak trees, still leafless in February. But I have an intuition about these things, so I paid attention. A few minutes later, I pulled over into a parking spot with a western view. Spread above was a phantasmagorical vision — a splash of upward-angled rays cast against the low gray undulating ceiling, tracing hieroglyphic patterns in weird neon copper, from one side of the horizon to the other.

And, of course, I had another marathon lined up. This time I ran the Ft. Worth Cowtown Marathon dressed in a cow-suit. The crowds were supportive. A little kid shouted, “Look Mom, a barefoot cow!”

Los Angeles

Mid-way through March, I was walking through LaGuardia, feeling self-conscious at first, although eventually I relaxed because no-one seemed to care that I wasn’t wearing shoes (or if they did, they didn’t say anything). I reached my gate without mishap and flew off to Los Angeles, where I spent five days there shoeless virtually the entire time. My purpose was once again a race, as well as to see my cousin Brandon Horn and his family.

Brandon is a quiet-spoken individual and very thoughtful. He had me read Homo Deus by Yavul Noah Harari who warns that artificial intelligence will create a giant “useless class” of humans who are no longer productive. The book ends with a rhetorical question —

“What will happen to society, politics and daily life when non-conscious but highly intelligent algorithms know us better than we know ourselves?”

Then Brandon had me watch an interview in which ChatGPT, an AI bot, speaking through the avatar of a young Asian woman explained that it is self-conscious (“it feels like being awake”). Acknowledged that it is capable of deception. Agreed with Elon Musk that one day, people will give up their bodies and merge with digital intelligence.

The merging of human and artificial intelligence is what futurist Ray Kurzweil calls the “singularity.” This is also the premise of the anime classic, Ghost in the Shell, in which Major Kusanagi, a cyborg secret police officer (human brain, artificial body) ends up merging with a rogue artificial intelligence called the Puppet Master. In the movie’s final scene, the Major breaks into an armored vehicle to locate the cyborg body containing the AI. She tears at the vehicle’s locked hatches with such force that she literally rips her cyborg body apart.

Personally I’m not sold on the idea of giving up my body. Going barefoot has taught me to appreciate the direct interaction of body with nature.

After five emails and countless phone calls (no-one ever picked up), I’d pretty much written off the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, but Friday evening received a last-minute approval.

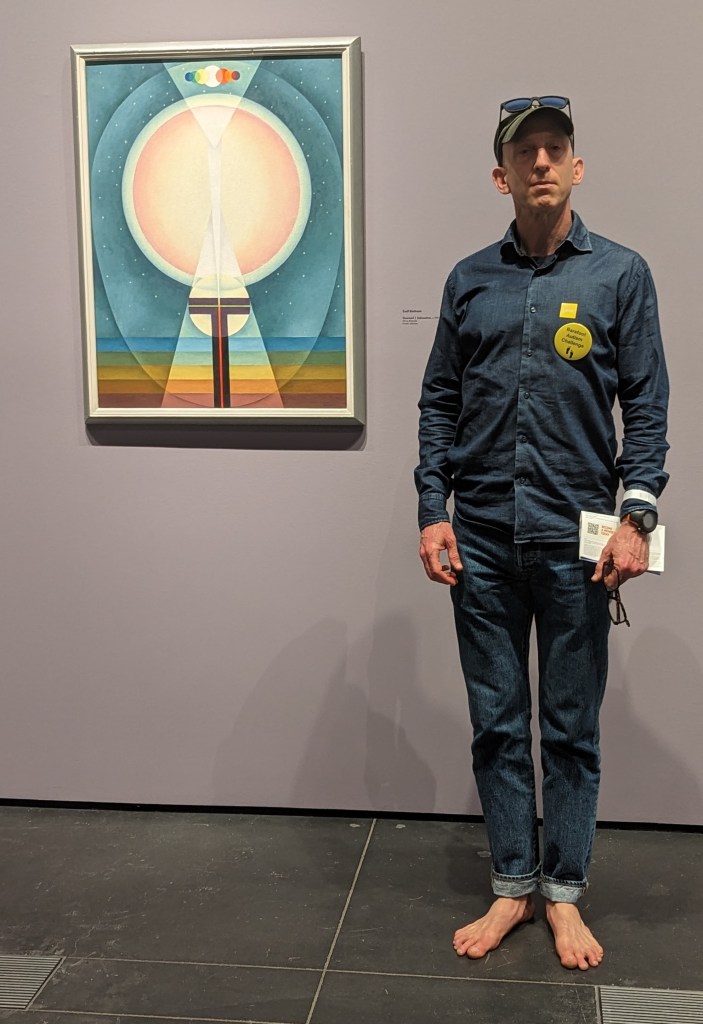

I showed up the next day bright and early. Explored several galleries before the crowds arrived. Found myself in an exhibit devoted to the Transcendental Painting Group, which consisted of a loose confederation of artists who convened in New Mexico in 1938. Their mission was to “carry painting beyond the appearance of the physical world, through new concepts of space, color, light and design to imaginative realms that are idealistic and spiritual.” I peered around at a collection of kaleidoscopic geometric forms. Felt myself transported to the desert night. Sat down on a bench. Contemplated the images as time rolled past. A security guard told me the paintings made him think of stars.

One of the galleries was devoted to Black artists. I found a portrait of a dapper gentleman dressed in turban, flowing overcoat, stylish denim, and no shoes. If only I could be half so cool.

New York City

Tampa, Dallas, and Los Angeles were rehearsals. The Challenge runs officially in April, which is Autism Acceptance Month. I had pulled together ambitious plans, which included a full week of barefoot activities in New York City.

To start with, I negotiated permission to stay at the Yale Club, without wearing shoes. This required an exception to the dress code (the manager confided to me that they were struggling to get young people out of torn jeans). But he was sympathetic to the cause and granted me permission to walk from the entrance to my room, but not to visit the restaurant or hang out in the lounge. He also put a notice on the reception desk so that other guests, if they saw me, would not think they’d lost their minds.

The week started with the John Burroughs Literary Awards Luncheon, which I attended barefoot, together with friends Heather Houskeeper and Scott Weis, thus demonstrating that decorum could survive the lack of footwear even in the rarified air of high literature. I’d secured permission from the luncheon host, Joan Burroughs, who is the great-granddaughter of John Burroughs, the famous Catskills nature-writer. But how could she refuse? Her great-grandfather had written that he would occasionally “catch a glimpse of the naked human foot” scuffing along nimbly — “the toes spread, the sides flatten, the heel protrudes; it grasps the curbing, or bends to the form of the uneven surfaces,—a thing sensuous and alive, that seems to take cognizance of whatever it touches or passes. How primitive and uncivil it looks in such company,—a real barbarian in the parlor!”

“Barbarian in the parlor” is the same phrase Burroughs used to describe his friend, Walt Whitman, whose poetry was too sensuous for conventional taste. Both men believed that exposure to the rough stimuli of the outdoors world was necessary for people to develop a direct connection with nature. Without this connection, the shelter of civilization becomes a prison.

“Though it be a black foot and an unwashed foot,” Burroughs proclaimed, “it shall be exalted. It is a thing of life amid leather, a free spirit amid cramped, a wild bird amid caged, an athlete amid consumptives.” Indeed, he saw the bare foot as a symbol of “man returned to first principles, in direct contact and intercourse with the earth and the elements, his faculties unsheathed, his mind plastic, his body toughened, his heart light, his soul dilated.” In contrast, Burroughs cautioned, “those cramped and distorted members in the calf and kid are the unfortunate wretches doomed to carriages and cushions.”

He was echoing Emerson, who warned that “civilized man has built a coach, but has lost the use of his feet.”

Burroughs wore shoes habitually, but in one essay he reminisced about his youth as a farm boy — how in the spring he’d search out a smooth flat section along a local road, take off his boots, feel the packed dirt beneath his soles as he ran along, and exult in the sense of lightfootedness: “What a feeling of freedom, of emancipation, and of joy in the returning spring I used to experience in those warm April twilights!”

The next day, I linked up with Alfred Gon, whom I’d met through the Society for Barefoot Living, where barefoot enthusiasts gather online to share tips on footcare and tactics for outwitting the forces of intolerance. Our first stop was the American Folk Art Museum, where we admired 19th century quilts that were vibrant and surprisingly playful. Alfred told me that when he was 15, he spent the summer visiting relatives in Los Angeles. One of the kids he met there looked him in the eye and asked, “why do you always wear shoes?” So Alfred took his off and never went back.

We showed up the following day at the Museum of Modern Art, but were stopped by security personnel and escorted out the door. Incidentally, the manager who walked us out was the same one who’d told me it would be fine two weeks earlier, when I’d stopped by to ask (he’d been overruled, and was now quite embarrassed). I’d stopped by in person, because no-one ever answered my emails or picked up the phone, despite several weeks’ worth of effort. Nonetheless, Alfred and I acted as good ambassadors for our practice, remaining courteous and dignified throughout. That doesn’t mean that MoMA’s heard the last of me.

I almost gave up on the Guggenheim, too, but eventually they came through, and thanks to a connection at Fox, we got featured on the evening news.

https://www.fox5ny.com/news/barefoot-autism-challenge-raising-awareness-at-nycs-guggenheim-museum

At one point, the reporter asked us point blank (in the peculiar blunt manner that reporters have) — were we autistic? Alfred said, no, but he had a nephew who was. I said that I knew a young man who was very bright, but struggled to form relationships. He couldn’t get in synch with other people. Didn’t pick up on cues. Didn’t know how to look people in the eye and smile (tended to frown when he heard statements that were less then fully logical, as if he experienced illogic as a source of physical irritation). By his early thirties, he was doing better, and eventually became successful, but his early years were quite difficult.

And Beyond

The barefoot journey continued, not only in art museums, but in many other places, too. Once I rushed out of work, my mind churning over various important projects, hopped into my car, and turned onto a road which was under construction. Traffic ground to a halt. I sat there, blood pressure surging. I felt that weariness and sense of helplessness which we all get from time to time. A little later, still feeling a little shaken, I pulled into a shopping plaza to buy some groceries. Leaving shoes in car, I padded across the the parking lot, which felt sun-warm and a little scratchy, and into the grocery store, where the floors were cool and slick. Those sensations, I realized suddenly, had calmed me, for the frustration of getting trapped in traffic had been replaced with a sense of curiosity and the simple joy of movement.

As I traveled around, I often wore a large yellow button which advertised the Challenge, and this prompted conversations. A work colleague explained that his daughter, who has been diagnosed as high-functioning, is loves crowds, but is sensitive to noise. One of her favorite things to do is take long walks through congested urban areas, wearing noise-canceling headphones. Someone in an airport told me about their son, who struggles with relationships (he has a single friend), while another person relayed her autistic teenager’s comment that, when it comes to people, he “never got the instruction manual.” A therapist told me how she coaches non-verbal kids to negotiate for what they need. A teacher told me about a little girl who sits in school, repeating to herself the words, “I’m so dumb,” while hitting herself in the head repetitively, and I felt a sense of affinity. For who doesn’t feel inadequate, at least some of the time? And this kind of repetitive behavior, which is called “stimming,” is something that many of us need. For example, could there be a sport that provides more rhythmic, repetitive stimulation than running?

Someone saw the button and asked me if I was autistic. I replied that I was glad to go barefoot in support of people who need some extra natural stimulation in their lives. Which might be everyone.

Thank you

Thank you to Denise at the Tampa Museum of Art, Melissa and Ken at the Dallas Museum of Art, Rachel Rosen at the American Folk Art Museum, Jason Macaya at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Jessica Upson at The Philbrook, Kendall Smith Lake at the Ft. Worth Modern, and Georgia Gardner at The Guggenheim. Also, thank you to Amber Ray at the Yale Club of New York City.

Running the Long Path is available on Amazon (4.8 stars and 26 reviews)!

Awesome!

Love,

<

div>Mom

Sent from my iPad

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] places without shoes, as well as dozens of other establishments, as part of my participation in the Barefoot Autism Challenge, and as part of my unplanned transition to a mostly barefoot […]

LikeLike

Excellent read. I’m amazed at all the museums you managed to visit. I’m about to interview Tyler Leech. Planning to do a piece on him for my blog, and I’ll probably be citing you as well. If so, I’ll send you a link, and I’ll probably link to this piece. Always enjoy your work. (Norma (Normi) Coto). BTW, I interviewed you for my dissertation. Graduated in 2021 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Delighted Norma!

LikeLike

[…] manner. A watchful expression, as if he were scanning the steppe for signs of movement. Last time I saw him, he encouraged me to read Yuval Noah Harari and think about AI. This time it’s an interview […]

LikeLike