This Thanksgiving, if you’re spending time with family and friends, that’s fine, but if you consider yourself an “Epicurean,” that is, someone who places a high value on fine food and drink, unfortunately, I can’t find any philosophical justification for your preferences.

As a fan of the Stoic philosophers of Ancient Greece and Rome, I thought it was only fair to give the other side a fair hearing, and so I set out recently to learn something about Epicurean philosophy, thinking it would be a study in contrast. After all, the dictionary defines Stoicism as endurance of pain without complaint, while Epicurean signifies devotion to sensual pleasures, especially fine food and drink. But I discovered, to my surprise, that this is not the real story.

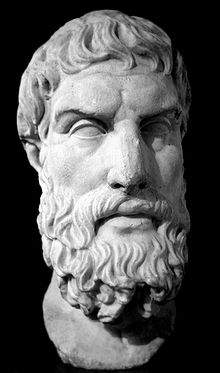

A Greek philosopher who lived in Athens, Epicurus (340-271 BC) was the founder and namesake of the school of philosophy known as “Epicureanism.” It’s true that Epicurus advocated pleasure as the primary goal of life. He wrote that, “Pleasure is our first and kindred good. It is the start-point of every choice and of every aversion.”

But let’s be careful about leaping to conclusions. Epicurus was celibate and a vegetarian. He wrote that “plain fare gives as much pleasure as a costly diet” and he recommended a “simple and inexpensive diet” as supplying all that is needed for health. In fact, he thought the “highest possible pleasure” is conferred when bread and water are brought to hungry lips.

What cannot be satisfied is not a man’s stomach, as most men think, but rather the false opinion that the stomach requires unlimited filling.

— Epicurus

I have bad news for chefs, food critics, gourmets, gourmands, connoisseurs, and all other foodies: Epicurus had a totally different idea of pleasure from what you think. What he was really advocating is a mental state which the Greeks called ataraxia, which translates roughly as “robust tranquility.” Ataraxia is very similar to the Stoic ideal of apatheia, which translates as “equanimity” or freedom from disturbing passions (it does not have the negative connotations of the modern word, “apathy.”)

By pleasure we mean the absence of pain in the body and of trouble in the soul. It is not an unbroken succession of drinking-bouts and of merrymarking, not sexual love, not the enjoyment of the fish and other delicacies of a luxurious table, which produce a pleasant life; it is sober reasoning, searching out the grounds of every choice and avoidance, and banishing those beliefs through which the greatest disturbances take possession of the soul.

— Epicurus

Even further, there’s a role for pain in Epicurus’ vision of the pleasureful life: “Often we consider pains superior to pleasures when submission to the pains for a long time brings us as a consequence a greater pleasure.” This was a comment on exercise and training, which the Greeks called ascesis, the root of the modern word, “asceticism.” Ascesis didn’t mean a lifestyle of denial, but referred to the practice of developing physical endurance, going without food and drink, and undergoing the extremes of heat and cold in order to toughen the body and sharpen the mind.

For Epicurus, living the good life had little to do with fancy food, and everything to do with self-discipline, deliberation, virtue, and surrounding yourself with like-minded individuals:

Of all the means which are procured by wisdom to ensure happiness throughout the whole of life, by far the most important is the acquisition of friends.

— Epicurus

If you’re a foodie, you don’t have to like or agree with Epicurus, but you should recognize that he walked his talk. As he lay dying, he wrote to a friend:

I have written this letter to you on a happy day to me, which is also the last day of my life. I have been attacked by a painful inability to urinate, and also dysentery, so violent that nothing can be added to the violence of my sufferings. But the cheerfulness of my mind, which comes from the recollection of all my philosophical contemplation, counterbalances all these afflictions.

— Epicurus

It turns out that Epicureans and Stoics are pretty similar.

In the spirit of full disclosure, I do appreciate good food, but see no point in complicating things. Healthy fare like grass-fed beef or wild salmon is already perfect — even without a speck of spice, seasoning, sauce, or salt. A crisp Hudson Valley apple doesn’t improve when baked into mush, doused with sugar, and thrown into a pie. A slice of watermelon on a hot summer day needs nothing else.

Regardless of philosophy, I wish everyone a wonderful Thanksgiving, but listen to Epicurus: the holiday’s not about the food!

Sources: Max Bollinger, The Essential Epicurus, 2014, and Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, 10.22 (trans. C.D. Yonge)

Great post! Most people misunderstand this philosophy completely of which I’ve previosuly been guilty of. The notion of appreciating ones self-discipline and needing less of external satisfaction is something we should all try to practice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] have been warning about the perils of comfort since the Cynics, Stoics, and Epicureans of Ancient Greece. These warnings were repeated by 19th-century American Transcendentalists, […]

LikeLike

[…] spiritual development. The ultimate goal was to achieve the states of “ataraxia” (tranquility, serenity, freedom from worry) and “apatheia” (equanimity, composure, freedom from […]

LikeLike

[…] The pavement smoothed out after a little while and I moved somewhat more quickly, passing a few people here and there. Up ahead a runner was wearing a red shirt which said “Beef-loving Texans.” This seemed more representative of the typical Texas attitude than the lone vegan activist on Pioneer Plaza. Beef is a big deal in Dallas, as I’d discovered at a recent business dinner. The waiter told us this restaurant was one of a very small number of places in the U.S. serving authorized Kobe beef, at $75 per ounce. I resisted the temptation to order a $900 steak, although I toyed with the idea of sampling a single ounce just to see what made it so special — but decided this was a taste worth not developing. […]

LikeLike

[…] and Yes to a simple, inexpensive, healthy diet (which was, incidentally, what the Greek philosopher Epicurus used to […]

LikeLike