In his noteworthy 2020 book, Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization, Scott Barry Kaufman builds upon the work of pioneering humanist Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) to offer a 21st-century definition of “transcendence,” together with a review of scientific techniques for healing, growth, and self-actualization.

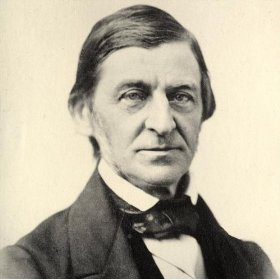

In a previous article,[i] I offered a quantitative definition of transcendence, yet one that was inspired by the 19th-century American Transcendentalist tradition, whose most famous authors include Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, John Burroughs, and John Muir. Staring with a metaphor for transcendence, I suggested the act of climbing a mountain, crossing a range, reaching the other side. Although to be clear, “transcendence” is not a place you reach. It is not a target end-state. Better to think of it as a vector, consisting of a direction (“up”) and a distance (how far you can climb), except we’re interested in maximizing happiness, rather than elevation. The best way to maximize happiness, according to the American Transcendentalists, is to spend time in nature. This is because the Transcendentalists saw exposure to “wild” environments as necessary for developing spiritual power. Bear in mind the Transcendentalists were writing during the mid- to late-19th century, when America was rapidly industrializing and urbanizing, and the frontier was already starting to close. Continue reading “Transcend What?”