How to Allocate Your Time, Avoid Burn-out, Boost Your Spiritual Power, and (Possibly) Make it to the Other Side

The word “transcend” is derived from the Latin “trans” (across) and “scandere” (to climb). In a sense, the word means to cross a mountain range. Like the scout William Lewis Manly, who found a route across the Panamint Mountains bordering Death Valley, made it to coastal California, and returned with food to save his comrades who were starving. This was in 1849.[1] Go back further in time, and it’s not hard to imagine our hunter-gatherer ancestors staring at a mountain wall, wondering what they would discover on the other side. If they could find a route across.

Today we use the term, “self-transcendence,” in a more general sense, wondering if we could become tomorrow, in some way, better, stronger, happier, and more productive than we are today.

American Transcendentalism was a 19th century philosophical movement which included authors such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, John Burroughs, and John Muir, among others.

The central premise of Transcendentalist philosophy was that people could achieve self-transcendence by drawing spiritual power from nature. In this regard, the Transcendentalists were reacting to problems they perceived in 19th century America, where industrialization and urbanization were spreading rapidly, and the frontier was shrinking and would soon close. Among the clerks, mechanics, priests, professionals, and others who spent their days indoors, Thoreau remarked on what he perceived as “lives of quiet desperation.” Emerson railed against the conformity, timidity, anxiety, and toxic egotism he associated with conventional society. Whitman was blunt – writing under the pen name Mose Velsor, he warned that a sedentary indoors lifestyle devoted purely to mental work was “death.”

Fast forward to today. The Transcendentalists are still remembered, but the popular narrative has shifted. The new philosophy is Transhumanism – the hope that we will transcend our limitations through technology. Transhumanism culminates in the “Singularity” – the point at which humans and machines merge.

Exhibit 1: Search Trends Show Transhumanism Eclipsing Transcendentalism

Source: Google Trends

But is Transhumanism a good thing? Futurologists like Ray Kurzweil eagerly anticipate the vast computational power and radical life extension that he believes await us. Elon Musk says we have no choice but to merge, due to the bandwidth limitations of the human brain, which will prevent us from competing effectively against machines.[2] The late physicist Steven Hawking warned of existential risk. He feared that artificial intelligence “could spell the end of the human race.”[3]

With the stakes so high, it’s fair to ask whether Transcendentalism is still relevant, and if so, how would you put it into practice?

Allocating Time between Nature and Technology

The practice of Transcendentalism starts with spending time outdoors. Thoreau commented that he needed to spend at least four (4) hours outside every day “sauntering through the woods and over hills and fields” to preserve his health and spirits. He could not spend a full day indoors “without acquiring some rust.”[4]

Everyone has 24 hours per day to play with. We’re constantly making decisions about how to allocate this time. At heart these decisions are about trade-offs. We illustrate this point in Exhibit 1. For simplicity we assume that people have 12 hours per day, excluding sleep, meals, and hygiene, to allocate between “Nature,” which refers to a natural environment, such as forest, grasslands, or mountains, and a “Tech environment,” which refers to a typical dwelling or workplace set up to maximize productivity.

The diagonal line in the diagram is the “budget constraint” – it represents the various combinations of hours that could be allocated to each category while adding up to 12. Point A on the chart refers to Thoreau, or someone like him, who we’ll assume allocates 8 hours per day to nature (comfortably above his 4-hour minimum).

The question for the rest of us — where on this line should we be?

The answer — pick the point on the diagonal line that maximizes your happiness. The curving lines in the diagram are like contour intervals on a topographic map, except here they trace levels of equal happiness instead of levels of equal elevation, and higher means happier. For Thoreau, point A on the diagonal line gets him to the crest of the ridge formed by the contour lines, which is the highest possible point he can reach. In contrast, point B represents an allocation of fewer hours to nature, which would correspond to a reduced state of happiness for Thoreau. Presumably this is where he thought most people were spending their lives, quietly desperate because they didn’t get outdoors enough.

Happiness comes from many sources. In nature — the sight of fiery autumnal foliage or a brilliant butterfly, a breeze that cools your sweat, the view from a mountain summit which lets you grasp the lay of the land. In a tech environment – the satisfaction of solving a problem, advancement in rank and social recognition, and, of course, money and the sustenance it provides. The contour intervals in the diagram represent happiness levels resulting from both sources. The shape and position of the contour lines can be different for different people, and for the same person, they can change over time.

To state the obvious, not everyone has the same priorities as Thoreau. Exhibit 3 shows the optimal time allocation decision for someone who’s focused on the benefits of work, reflected in a different pattern and orientation of the contour lines. Maybe this person needs money and benefits to support a young family, which Thoreau did not have. Maybe this person will feel differently when the children have left home.

Exhibit 2: Optimal Time Allocation for a Transcendentalist

Point A represents the optimal time allocation for this individual, consistent with the highest point on the contour lines, which indicate happiness. Point B is a suboptimal point, which represents a lower level of happiness.

Point A represents the optimal time allocation for this individual, consistent with the highest point on the contour lines, which indicate happiness. Point B is a suboptimal point, which represents a lower level of happiness.

Exhibit 3: Optimal Time Allocation for Someone Who Values Employment

Today most occupations are practiced indoors, with fulltime outdoor jobs accounting for only 4% of the total, these being mostly in construction and landscaping, although many jobs have some outdoors exposure (such as delivery and service personnel and first responders).[5] Additionally, most people eat and sleep indoors. As a result, the vast majority of modern human life takes place within enclosed environments. In fact, Americans spend on average 93% of their time inside, according to a recent survey. Specifically, 87% of their time in buildings, and 6% in vehicles (Exhibit 4).[6] If this seems like a shockingly high number, bear in mind, even for someone like Thoreau who spent 4 hours outside per day, but who slept and ate inside, fully 83% of their total time would be spent indoors. For our paleolithic ancestors, the ratio of time outside would have been 100%, unless you gave them credit for sleeping in caves or under ledges.

Yet people haven’t fully forgotten nature. According to the Outdoor Industry Association, 168.1 million people participated in outdoor recreation activities in 2022, accounting for 55% of the US population aged six and older. Furthermore, most categories of participation saw growth in 2022. But the frequency of outings edged down, continuing a negative long-term trend – outings have fallen steadily from 85 per person in 2013 to 71 in 2022.[7]

Exhibit 4: Americans Spend 93% of Their Time Indoors

NHAPS = National Human Activity Pattern Survey, published by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in 2001

NHAPS = National Human Activity Pattern Survey, published by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in 2001

Walking through the streets of Manhattan in the late 19th century, Walt Whitman responded to the quality he saw in the crowds: “alertness, generally fine physique, clear eyes that look straight at you, a singular combination of reticence and self-possession, with good nature and friendliness.” These were qualities he attributed to the outdoors lifestyle of the time, with people working in “regular contact with out-door light and air and growths, farm-scenes, animals, fields, trees, birds, sun-warmth and free skies.” He linked this lifestyle to culture and political organization, writing in his memoir that “democracy most of all affiliates with the open air, is sunny and hardy and sane only with Nature — just as much as Art is.” [8]

The question is what happens to people as their connection with nature attenuates. On this point, Whitman was emphatic — “I conceive of no flourishing and heroic elements of Democracy in the United States, or of Democracy maintaining itself at all, without the Nature-element forming a main part — to be its health-element and beauty-element — to really underlie the whole politics, sanity, religion and art of the New World.”

Variability of Experience in Natural and Tech Environments

As Whitman’s comment illustrates, the Transcendentalists regarded nature as a necessity. Not a luxury. Further, they did not conceive of nature as merely a pastoral landscape of meadows and rolling hills – it was to them a source of “wildness.” This meant variability. Discomfort. Risk. Extremes of temperature. Storms. Predatory animals. Poisonous plants and insects. Hunger. Thirst. Fatigue. Thoreau argued that the “tonic” of wildness consists of “witnessing our limitations transgressed.” Or, as we might say today — getting pushed outside your comfort zone.

The purpose of an artificial environment is precisely the opposite — to shield us from nature’s rough stimuli. Sitting in ergonomic office chairs in well-lit, climate-controlled workspaces, with food and drink within reach, we are spared physical discomfort so that we can focus our energy on the work at hand and maximize productivity.

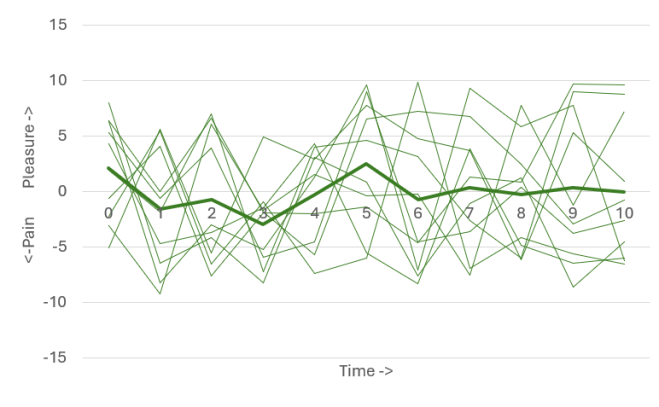

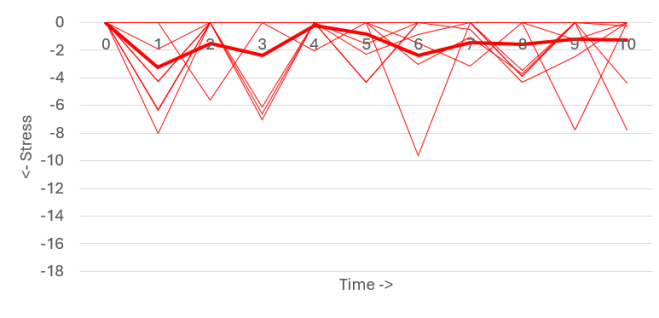

To illustrate the contrast between natural and tech environments, we constructed a simulation model of sensory experience. The model generates a random outcome ranging from a low of -10 (extreme discomfort) to a high of +10 (extreme pleasure) for ten sequential time periods. Random because nature is full of surprises. Exhibit 5 shows several iterations of the output, to give a sense of the wide variability of sensations that might be experienced in the wild. Think of these numbers as representing the pleasure and pain from shifting weather conditions – one moment a sweltering hot and muggy afternoon, the next a cooling breeze, and then a thunderstorm pelts you with cold rain and hail. Or think of these numbers as representing the variations in hunger and satiety experienced by our hunter-gatherer ancestors as they roamed the landscape in search of food – or as the pleasurable sensation of walking barefoot on grass followed by the sting of biting flies.

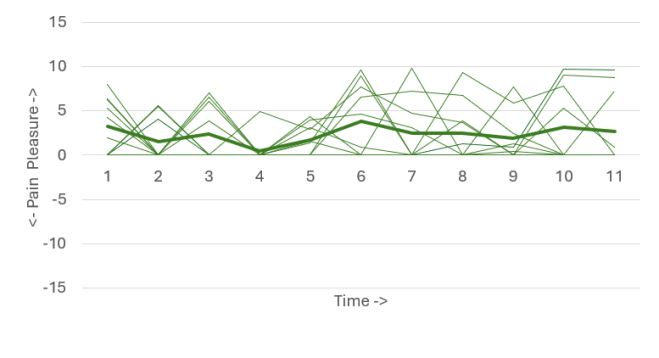

Next we ran the simulation model for a technology-enhanced environment, such as a house, office, laboratory, or workshop. Starting with the same variability of pleasurable sensations, we truncated the output at zero, to reflect the highly-controlled nature of these environments, where there is virtually no pain. Sources of discomfort have been eliminated by heat, air-conditioning, carpets, comfortable furniture, and vending machines full of snacks and drinks. The results are shown in Exhibit 6. Clearly, the variability of sensations is significantly lower than in the natural setting.

The shielding effect of technology goes well beyond our physical environment. For example, consider the use of drugs to manage the variability of mental states. In 2020 20.3% of adults sought treatments for mental health issues, and 16.5% took prescription medications, according to the CDC.[9] These medications included anti-depressants, which 13.2% of Americans were using in 2018, up from 7.7% in 1999. 18% of adults take prescription sleep medicine.[10] Among illegal drugs, the most popular is marijuana, which roughly 14% of the population reports taking within the last year.[11] And legal drugs like caffeine, alcohol, nicotine, and now THC are ubiquitous.

Exhibit 5: Simulated Pleasure/Pain Levels in a Natural Environment

The diagram shows multiple simulated levels of sensations, ranging from painful to pleasurable, over ten time periods.

The diagram shows multiple simulated levels of sensations, ranging from painful to pleasurable, over ten time periods.

Exhibit 6: Simulated Pleasure/Pain Levels in a Tech Environment

Nature and Happiness

If technology shields us from pain and helps us be productive – what’s wrong with that?

The challenge is that happiness depends on contrast. Writing in 1930, Sigmund Freud explained, “We are so made that we can derive intense enjoyment only from a contrast and very little from a state of things.”[12]

For example, if you were living outdoors and suffering through a difficult winter, when springtime temperatures finally reached 68 degrees, you would experience bliss, whereas in an office building with thermostat set to 68 F year around, the same temperature would never evoke a reaction. Recall from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, how Charlie Bucket’s family was so poor all they had to eat was bread and margarine for breakfast, boiled potatoes and cabbage for lunch, and cabbage soup for supper. Not surprisingly, for young Charlie an occasional taste of chocolate was a source of immense joy. But if you ate chocolate for breakfast, lunch, and dinner every day, the taste would be meaningless. (By the way, researchers have found that rats allowed to gorge themselves on an unlimited diet of high-calorie foods started out happy, as measured by electrodes applied to their brains, but after a period of time became chronically miserable, as well as fat.)

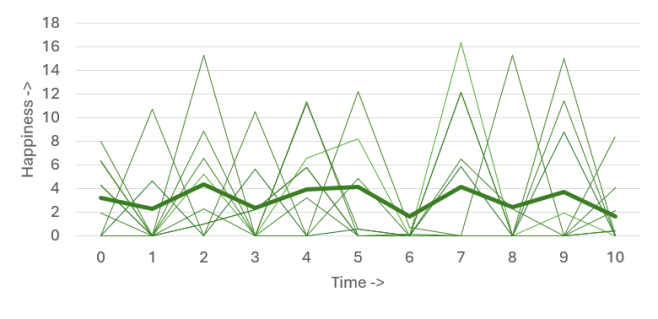

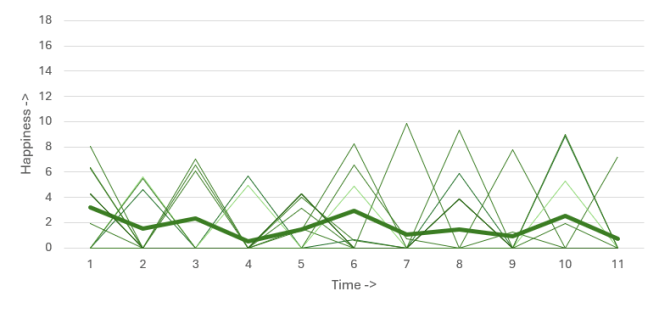

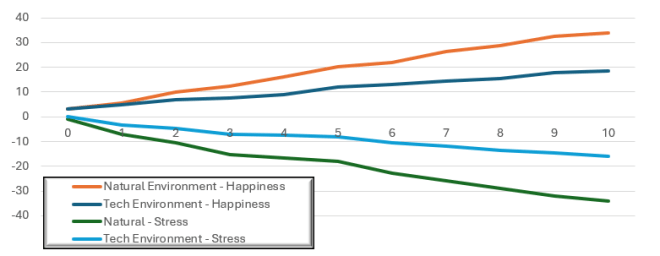

In the simulation model, we estimate happiness by calculating the increase in pleasure (or decrease in pain) from one period to the next. The bigger the positive change in sensation, the greater the resulting happiness. Using this definition, the model shows much higher levels of happiness in the natural than in the high-tech environment (Exhibits 7 and 8). Put simply, the natural environment is intense, with enormous contrast between painful and pleasurable sensations, whereas the high-tech environment is physically monotonous.

Exhibit 7: Simulated Happiness Levels in a Natural Environment

Happiness is defined as the increase in pleasure (or decrease in pain) from one simulated time period to the next.

Happiness is defined as the increase in pleasure (or decrease in pain) from one simulated time period to the next.

Exhibit 8: Simulated Happiness Levels in a Tech Environment

Our simulation model almost certainly understates the impact of technology for people use it not only to eliminate discomfort, but to intensify pleasure. To the max. Consider the Standard American Diet (also called the “Western Pattern Diet”), which includes a high quantity of sweets and ultra-processed foods engineered to be “hyper-palatable.” Taken to the extreme, this kind of diet would be represented in our simulation model with sensations that are consistently at extremely pleasurable levels (say, nothing but +9 and +10). As a result, contrast would be compressed to almost nothing, and happiness would almost fully disappear, at least with respect to diet.

Exhibit 9: Typical Sweets in the American Diet

Source: NIH, accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK588789/

Source: NIH, accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK588789/

Sensory amplification runs rampant in modern life. It’s not just food. Commenting on the literature of his time, John Burroughs complained, “everything is bedecked and bejeweled. Nothing is truly seen or truly reported. It is an attempt to paint the world beautiful. It is not beautiful as it is, and we must deck it out in the colors of the fancy.” In a similar vein, Whitman drew a parallel between the modern writer, who tries to put in “as much taste, perfume, piquancy, as he can” and the famer who crossbreeds species in order to intensify the scents and hues of flowers and the tastes of fruits. Yes, these techniques produce “the greatest immediate effect,” but Whitman cautioned they are not the way of Nature, whose flavors and fragrances are “faint and delicate.” It’s as if in a world with limited contrast, where every sensation is already a +10, we’ve got to somehow push things to +11, to satisfy a raging hunger for even the slightest contrast.

Nature and Stress

If nature produces higher levels of happiness, it’s fair to say it’s also the source of stress, ranging from snakebites to starvation, from disease and injury to violent death. We estimate stress in the simulation model by calculating the decline in pleasure (or increase in pain) from one time period to the next. Based on the same randomly-generated sensations we started with above, Exhibits 10 and 11 show, unsurprisingly, much higher stress levels in nature than in a tech environment.

Exhibit 10: Simulated Stress Levels in a Natural Environment

Stress is calculated as the decline in pleasure (or increase in pain) from period to period, based on the random sensations generated in multiple iterations of the simulation model.

Exhibit 11: Simulated Stress Levels in a Tech Environment

To sum up, nature is intense – the contrasts between pleasurable and painful sensations drives high levels of both happiness and stress, while the highly controlled environments in which people spend most of their lives today produce a much narrower range of sensations. This point is illustrated in Exhibit 12, where we show happiness and stress on a cumulative basis, as experienced over the ten time periods in the simulation model.

Exhibit 12: Cumulative Happiness and Stress Levels in Natural and Tech Environments

As a caveat to Exhibit 12, extremes of stress can correspond to injury and early death. Further, there are other sources of happiness and stress not considered in the simulation model, which is limited to physical sensations — success or failure in business ventures, investments, and other work-related projects, relations with friends, family members, and community members, participation in the arts, and so on.

For these reasons, we wouldn’t want to take the Transcendentalist message to an illogical extreme – for they did not call for the wholesale abandonment of modern technology. They did not advocate for a return to stone age culture and authentic paleolithic lifestyle. They did not argue that humanity took a wrong turn with agriculture, as anarcho-primitivists like John Zersan believe[13]. Rather, the Transcendentalists questioned their contemporaries’ time allocation to nature, which in the 19th century was already starting to diminish. They warned that losing connection with nature posed an existential trap — in which the prioritization of comfort would lead not to happiness, but to dependence, weakness, timidity, conformity, and decline.

Stress and Strength

Ask a weightlifter how she plans to get stronger, and she’ll answer — “train to failure,” meaning that she’ll lift the weights until she can no longer complete a repetition. This kind of training subjects the muscles to stress, including discomfort and the risk of strain. In turn, stress drives growth and development.

The body has many capabilities: we can keep ourselves warm in cold environments through thermogenesis involving brown adipose tissue (BAT)[14] — we can keep moving for long periods of time without food by metabolizing fat — we can walk and run for hundreds of miles. But if you don’t expose the body to cold, go without food, or train your legs, you will not develop these capabilities. Further, without exposure to these stressors, the capabilities will attrit.

The crux of the Transcendentalist argument is that stress makes you stronger — mentally, physically, and spiritually. Writing at the turn of the 20th century, John Burroughs argued that “life, power, longevity, manliness” and the qualities of “vitality” and “virility” arise from strain and struggle over generations – a conclusion inspired directly by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.

For those who worked indoors, Whitman recommended physical training, which he thought should be “a systematic thing through life.” The goal being to develop physical attributes, like “Herculean strength and suppleness.” To encourage a mindset that is “strong, alert, vigorous.” To foster spiritual qualities, like being “morally upright.” To partake in “universal joy and strength.”[15] Mental and spiritual strength were frequent themes for Emerson and Thoreau as well – they wrote about focusing on the present moment and avoiding toxic egotism. Today we use terms like mindfulness, gratitude, and flow state to describe the practice of self-management.

Earlier we talked about allocating time, within the strict constraint that only so many hours per day are available. Now let’s shift from time to the concepts of work, defined as the ability to exert force in a purposeful manner, and power, which is a measure of output, defined as work accomplished per unit of time. Greater strength means greater force, more work done, and a higher sustainable level of power output. And power is key to life, as Emerson pointed out in his essay on self-reliance — “Power is, in nature, the essential measure of right. Nature suffers nothing to remain in her kingdoms which cannot help itself.”[16]

To illustrate the possibility of self-transcendence, let’s return to our time allocation diagram, but with one change – we’ll switch the axes from hours to power. Now we can summarize the logic of transcendentalism: spending time in nature exposes us to stress – which makes us stronger – and greater strength translates into a higher level of power in our daily lives – which allows us to reach greater levels of happiness. This process is shown in Exhibit 13 by the green arrow, which pushes out the budget constraint, allowing the individual to operate at new state (point B) consistent with higher happiness than the prior state (point A).

This logic still resonates today, as we saw in the 168 million people who participate in outdoor recreation activities, representing 55% of the population aged six and over. Although the frequency of outings among this population has been declining in recent years. And one might well wonder about the other 45%.

Because without stress, strength ebbs. Power attrits. Happiness may start to fade. The red arrow in Exhibit 13 represents the risk of what we might call “burn out” – too much time spent in highly-controlled environments. Which leads to dependence. Weakness. Fear of stress. Regret for not having done more. Possibly the quiet desperation that Thoreau thought he saw in his contemporaries. Burroughs didn’t mince words — “where struggle ceases, the race or family is doomed.”[17]

Exhibit 13: Transcendence and Burn-out

Power is equal to work per hour. The green arrow represents “transcendence,” in the sense of developing higher power through training and/or exposure to natural environments, which shifts the budget constaint up and to the right, allowing a person to move from point A to a higher happiness level at point B. The red arrow represents “burn out,” in the sense of becoming weaker by avoiding exposure to stress, which results in lower happiness.

Nature and the New

Getting out into nature was not merely a time allocation priority for the Transcendentalists. It was also a metaphor for life.

Let’s step back and think more broadly about words like “natural” and “wild.” In The Practice of the Wild, American poet Gary Snyder acknowledges that “nature” has a very broad set of connotations, starting with the simple idea of “outdoors” and ultimately encompassing the entirety of the material world. Which includes people. And everything we create. Which means that there “is nothing unnatural about New York City, or toxic wastes, or atomic energy.” By this definition, everything we do or experience in life can be considered ‘natural.’[18]

But not everything is wild. Although Snyder struggles to pin down a specific meaning, instead presenting a list of synonyms. Undomesticated. Uncontrolled. Unintimidated. Self-reliant. Independent. “The word wild is like a gray fox trotting off through the forest, ducking behind bushes, going in and out of sight.”

For our purposes, let’s use “wild” in a prosaic sense to indicate environments which are uncontrolled, regardless of the physical setting. Wild environments are uncertain. Risky. Unpredictable. Subject to volatility and presenting a wide range of possible outcomes.

When you operate in a familiar and highly-controlled environment, you maximize productivity. In contrast, when you head off into the unknown, you will learn something new. To reflect the fundamental trade-off between productivity and risk-taking, economists use the term “exploration-exploitation dilemma”[19]. Animals, people, and organizations all face this dilemma. For example, animals must choose between grazing in one place, or ranging out in search of greener fields. Similarly, our ancestors, when they were situated in a valley with abundant food and shelter, would still have wondered what lay beyond the mountains – and would it be worth the effort and risk to go exploring? Companies face the same dilemma – they could distribute the cashflow thrown off by existing products, or spend it developing new products with the potential for higher profits, but no guarantee of success. The right answer to all such dilemmas depends on the nature of the time/power constraint and the shape of the contour lines for happiness (or profits). The wrong answer is to always default to the comfortable option regardless of the circumstances.

The Transcendentalists thought it was necessary to embrace the wild. They were inclined to favor exploring. Burroughs drew a parallel between a comfortable indoors life and narrow-mindedness, writing that “we are housed in social usages and laws, we are sheltered and warmed and comforted by conventions and institutions and numberless traditions.” This was not a good thing, in his opinion, for people with sheltered minds struck him as timid, conformist, evasive, insincere, and self-distrustful – indeed, he complained that “the fear of being unconventional is greater with us than the fear of death.” He likened contemporary artists to “potted plants” – colorful, but fragile and dependent.[20]

For Thoreau, the wild stood for opportunity. On his daily walks he found himself often orienting to the west, which was the direction of the American Frontier. “I must walk toward Oregon, and not toward Europe,” he wrote, then elaborated – “We go eastward to realize history and study the works of art and literature, retracing the steps of the race; we go westward as into the future, with a spirit of enterprise and adventure.”

He also linked the wild with creativity. “In literature it is only the wild that attracts us. Dullness is only another name for tameness. It is the untamed, uncivilized, free, and wild thinking in Hamlet, in the Iliad, and in all the scriptures and mythologies that delights us, — not learned in the schools, not refined and polished by art.[21] [22]

Emerson detested conformity and cared only for originality — “A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within, more than the lustre of the firmament of bards and sages.”

For the Transcendentalists, time in nature was not merely a necessity for bodily health and sanity, but part of an attitude that embraced uncertainty, opportunity, innovation, and change – rather than hiding from it. Well before the digital revolution, the Transcendentalists worried that their contemporaries were becoming too comfortable, both physically and mentally.

Transcendentalism in an Era of Technology

We’ve radically changed our world, but have we changed ourselves to the point that nature no longer matters?

“Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it,” Archimedes said, “and I can move the world.” This is the original conception of technology as leverage. The lever takes our limited human power and magnifies it immensely. But we still need our human strength, as puny as we may be, to apply force against the lever to move it. Further, there’s a risk – should the world start tilting unexpectedly – that the lever could swing the wrong way and strike us.

If we become too comfortable operating in highly-controlled environments, to the point that our strength weakens, we shy away from risk, we embrace dependence and fragility as our norms – then it’s conceivable that we could lose control of the machines.

But well before that happens, we’ll have to contend with technology’s disparate impact. Meaning that the rewards flow disproportionately to those who lead corporate and governmental organizations which control the resources needed to implement change at scale and which aggressively advertise and propagandize and sometimes spew misinformation. In this regard, we may need to fight against exploitation. If so, resistance requires a mental disposition that is vigorous and alert. Inner strength and determination. Confidence. If people disengage from nature – if they shy away from wildness, flinch in the face of stress, cling instead to sources of distraction – if we become weak and dependent, then we risk losing our sovereignty as individuals. Our agency. Our freedom to allocate our scarce hours and limited power as we see fit.

A theme of resistance runs throughout American Transcendentalism. Angered by the stifling traditional ritual and oppressive attitude within the Unitarian Church, Emerson rebelled –“Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist.” Thoreau put that principle into action, refusing to pay taxes to a government that supported slavery and war, for which he was briefly jailed. Whitman summed up his love for democracy with a rallying cry, later adopted by the nature-writer, anarchist, and monkey-wrencher Edward Abbey – “Obey little, resist much.”

Can individual freedom be sustained in a high-tech (highly controlled) environment? It’s not a question we can easily answer. It’s not a question we can safely ignore.

Into the Future

You could push back against our analysis. You could argue that the transition from wild to highly-controlled environments is just change. So deal with it. This is just the next phase of our evolution as a species.

Furthermore, the loss of outdoors intensity is surely replaced by the thrill of intellectual pursuits – scientists pushing the boundaries of our collective knowledge, managers developing innovative products and services, investors trading ever more complex derivative securities, political leaders promoting the next big thing. Writing in the 1970s, the popular futurist Alvin Toffler predicted that people would immerse themselves in work.[23] Of course, he probably didn’t have low-paying service jobs in mind, like being a Wal-Mart greeter, working in a chicken meat processing plant, or driving for a rideshare service.

Yet even for professionals, is indoors mental work as fully satisfying as the original human lifestyle? Clarence King was both a mountaineer and a highly respected scientist – indeed he was considered one of the rising stars of his generation – yet he lamented the all-consuming nature of his work. A comment from his diary in the waning days of the 19th century — “I am convinced that science goes on and progresses at the expense of those absorbed in her pursuit. That men’s souls are burned as fuel for the enginery of scientific progress. And that in this busy materialistic age the greatest danger is that of total absorption in our profession…We give ourselves to the Juggernaut of the intellect.” This problem seemed to him a consequence of a modern lifestyle that led to numbing of the senses and loss of tranquility. “Civilization!” King once joked to a friend. “Why, it is a nervous disease!”[24]

You could make the argument that for most people, the greatest source of happiness is family. To support their spouse and children, people will take on any manner of work. They’ll do whatever it takes. And there’s plenty of intensity and stress in raising and providing for a family.

But raising families seems to be going out of vogue, at least in highly developed societies. Many European and Asian countries were already witnessing negative population growth before the COVID pandemic, but afterwards, for reasons that are not clear, birth rates have fallen further. In many places by as much as 10%. In countries ranging from South Korea to Spain, birth rates today are so far below the replacement rate, that demographic collapse is foreseeable in the long term.[25]

No question, many of us feel confused by the rapid pace of change. Overwhelmed. Yet our next decision is as simple as it ever was — how should we spend the next hour?

Meanwhile, the mountains stand against the horizon. Cloaked in boreal conifers. Shrouded in mist. Dotted with lichens and wildflowers. Dappled with shadows of passing clouds.

They stand watch in our thoughts and dreams.

Calling to us, perchance, with songs of wonder.

Songs of what might lie on the other side.

[1] For a discussion of Manly’s adventure, see my Long Brown Path blogpost, accessible at https://thelongbrownpath.com/2015/10/23/before-badwater-william-lewis-manlys-1849-crossing-of-death-valley/

[2] https://www.cnbc.com/2017/02/13/elon-musk-humans-merge-machines-cyborg-artificial-intelligence-robots.html

[3] https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-30290540

[4] See Thoreau’s 1883 essay, “Walking”

[5] https://constructioncoverage.com/research/cities-with-the-most-outdoor-workers-2022#:~:text=According%20to%20data%20from%20the,%2C%20maintenance%2C%20and%20delivery%20occupations.and https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2023/32-9-percent-of-employees-had-regular-outdoor-exposure-in-2022.htm

[6] As referenced in https://www.buildinggreen.com/blog/we-spend-90-our-time-indoors-says-who

[7] 2023 OUTDOOR PARTICIPATION TRENDS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND KEY I INSIGHTS, accessed at https://outdoorindustry.org/resource/2023-outdoor-participation-trends-report/

[8] From Whitman’s memoirs, Specimen Days & Collect, as quoted in https://thelongbrownpath.com/2022/04/30/waltman-and-wilmington/

[9] https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db419.htm

[10] https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db462.htm

[11] https://www.statista.com/statistics/611152/illicit-drug-users-number-past-year-in-the-us-by-drug/

[12] Accessed at https://pressbooks.cuny.edu/philosophyashorthistory3/chapter/__unknown__-5/

[13] https://thelongbrownpath.com/2016/02/02/the-cry-of-the-anarcho-primitivists/

[14] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6466122/

[15] Walt Whitman, Manly Health and Training: To Teach the Science of a Sound and Beautiful Body (Regan Arts, New York: 2017)

[16] Emerson, “Self Reliance”

[17] https://thelongbrownpath.com/2016/05/15/burroughs-dont-lose-your-connectivity-with-nature/

[18] Gary Snyder. The Practice of the Wild: With a New Preface by the Author (Kindle Locations 113-114).

[19] https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0095693&s=03

[20] https://thelongbrownpath.com/2016/04/17/burroughs-on-barefoot/ and https://thelongbrownpath.com/2016/05/15/burroughs-dont-lose-your-connectivity-with-nature/#more-17323

[21] https://thelongbrownpath.com/2017/06/07/seeking-wildness/#more-35282

[22] From Thoreau’s essay, “Walking.”

[23] https://www.aei.org/articles/the-rise-of-the-single-woke-and-young-democratic-female/

[24] Thurman Wilkins, Clarence King: A Biography, Macmillan Company, New York, 1958

[25] https://open.substack.com/pub/alexberenson/p/the-baby-bust-is-worsening?r=7x92e&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=email

Study on rats gorging themselves from Mark Schatzker, The Dorito Effect: The Surprising New Truth About Food and Flavor, 2015

[…] [i] https://thelongbrownpath.com/2024/02/17/transcend-this-a-quantitative-interpretation-of-american-tra… […]

LikeLike