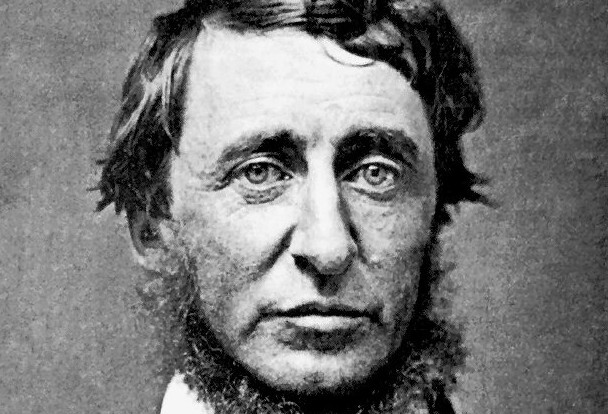

In a recent post, I compared a weekend spent hiking in the Catskills to Henry David Thoreau’s two-year sojourn at Walden Pond, as both were experiments in natural living and self-sufficiency.

But then my daughter Emeline brought to my attention a recent article entitled “Pond Scum.” The author, Kathryn Schulz, questions why we still admire the literature of a man who was mean-spirited and a fake. She summarizes her opinion in no uncertain terms:

The real Thoreau was, in the fullest sense of the word, self-obsessed: narcissistic, fanatical about self-control, adamant that he required nothing beyond himself to understand and thrive in the world. From that inward fixation flowed a social and political vision that is deeply unsettling.

— Kathryn Schulz, “Pond Scum,” 2015

Schulz condemns not only the man, but also his work, referring to Walden as “the original cabin porn,” that is, an unrealistic fantasy about country living and an act of hypocrisy — since he failed to disclose receiving supplemental food supplies from family members during his so-called experiment in self-sufficiency. The real story, according to Schulz: Thoreau was a “castaway from the rest of humanity,” a loner seeking to avoid the responsibilities of getting along with other people, and worst of all, his experiment was drab and depressing:

Ultimately, it is impossible not to feel sorry for the author of “Walden,” who dedicated himself to establishing the bare necessities of life without ever realizing that the necessary is a low, dull bar.

— Kathryn Schulz, “Pond Scum,” 2015

To be sure, Ms. Schulz isn’t the only person whom Thoreau has rubbed the wrong way. His contemporaries weren’t all fans. A friend said she loved Thoreau but didn’t like him. Robert Louis Stevenson called him a “prig and a skulker.” His mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson acknowledged that Thoreau had a bristly quality:

It seemed as if his first instinct on hearing a proposition was to controvert it, so impatient was he of the limitations of our daily thought. This habit, of course, is a little chilling to the social affections; and though the companion would in the end acquit him of any malice or untruth, yet it mars conversation.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1862

For his part, Thoreau admitted that he felt a certain meanness towards society and its obligations. But curmudgeonly manners and disinclination toward dinner parties doesn’t mean a man has no engagement with his fellow creatures, for Thoreau’s contribution to society came through his writings. The naturalist and essayist John Burroughs articulated this point in 1882:

The first effect of the reading of his books, upon many minds, is irritation and disapproval; the perception of their beauty and wisdom comes later. He makes short work of our prejudices; he likes the wind in his teeth, and to put it in the teeth of his reader. He was a man devoid of compassion, devoid of sympathy, devoid of generosity, devoid of patriotism, as these words are usually understood, yet his life showed a devotion to principle such as one life in millions does not show; and matching this there runs through his works a vein of the purest and rarest poetry and the finest wisdom. For both these reasons time will enhance rather than lessen the value of his contributions.

— John Burroughs, “Thoreau,” 1882.

Burroughs was prescient, and not only about Thoreau’s influence, but also in identifying those people, including Ms. Schulz, who react with “irritation and disapproval.” Burroughs continues:

He was of the stuff that saints and martyrs and devotees, or, if you please, fanatics are made of and, no doubt, in an earlier age, would have faced the rack or the stake with perfect composure. Such a man was bound to make an impression by contrast, if not by comparison, with the men of his country and time. He is, for the most part, a figure going the other way from that of the eager, money-getting, ambitious crowd, and he questions and admonishes and ridicules the passers-by sharply.

— John Burroughs, “Thoreau,” 1882

Thoreau’s dislike of the “money-getting, ambitious crowd” puts him at the center of a tradition in Western society dating back to the earliest philosophers of Ancient Greece, who warned against social ambition and materialism, advocating instead for self-discipline and the pursuit of virtue. And there are similar voices in many other cultures. Call them critics, our collective conscience, or pests if you will; they buzz loudly, but their numbers have always been small. Schulz is shooting high when she frets about Thoreau’s political vision:

A nation composed entirely of rugged individualists—so stinting that they had almost no needs, so solitary that those needs never conflicted with those of their compatriots—would not, it is true, need much governance. But such a nation has never existed, and even if nothing else militated against Thoreau’s political vision its impossibility alone would suffice.

— Kathryn Schulz, “Pond Scum,” 2015

It’s true that Thoreau’s admirers include libertarians, survivalists, and anarcho-primitivists — but does Schulz think they are working to reshape society? (does she think they will get Rand Paul elected?) She’s reading Thoreau too literally. And missing the point: he wasn’t calling on his contemporaries to abandon family, work, and society and live in a barrel. Rather, he was playing the gadfly, reminding people that you can make do with less, warning against excessive conformity, fighting back against “the Matrix.”

If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.

— Henry David Thoreau

What vision would Ms. Schulz prefer? Is she an advocate of conformism and materialism, a shill for the consumer goods industry? I watched her give a TedX talk entitled “Don’t Regret Regret,” in which she admitted that she got a tattoo once and immediately regretted it.

On his deathbed, Thoreau said, “I may say that I am enjoying existence as much as ever, and regret nothing.”

Evidently, the two would not see eye-to-eye.

For my part, I don’t aspire to follow precisely in Thoreau’s footsteps, but like him I seek to move forward in life and cover some ground.

One who pressed forward incessantly and never rested from his labors, who grew fast and made infinite demands on life, would always find himself in a new country or wilderness, and surrounded by the raw material of life. He would be climbing over the prostrate stems of primitive forest-trees.

— Henry David Thoreau, “Walking,” 1862

I agree with you. – EP

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with you, enjoy Thoreau, and have long admired asceticism and its mystic rewards.

While “Walden” might at times read like “The 4 Hour Workweek” as written by John Calvin, Schulz’s piece, though an excellent essay, is far better read as the satire even its title suggests.

Whitman is still my favorite.

You cover more ground than most.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think Thoreau – as influenced by the ancient Greeks – pursued the virtuous life, but of course, was not perfect in his day-to-day actions toward those pursuits. Schulz doesn’t seem to be willing to allow Thoreau those imperfections. As if pursuing virtue is something that should, by its nature, exclude – or transcend – the human condition. I mean heck, she gave in to the seduction of getting a tattoo! Wouldn’t that make her the pot calling the kettle black? In my eyes, yes…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am glad to see this post as I had read Schulz’s article the same week of your first Thoreau post and I was curious what your reaction would be.

I think one unspoken point of her article is that cultural figures often make their way into our pantheon of elites without a full understanding of the person. In Thoreau’s case, his ideas have lasted yet we read his work with no idea about who he was as a person. And as Schulz deconstructs him, one has to wonder, how did such a misanthrope become so beloved? I remember learning even in junior high school that Thoreau’s retreat to Walden was broken up with frequent trips back to town – not exactly the model of rugged individualism.

As you point out, we remember him for his writings and ideas, many of them thoughtful, relevant and valid. But is Thoreau the best we can do, given his seeming disdain for humankind?

For me, I would rather rally around and quote Burroughs, a decent writer and seemingly an affable friendly person. The fact that Burroughs rallied around Thoreau says more about Mr. Burroughs than it does about Thoreau. Burroughs was just a nice and welcoming person, willing to overlook transgressions.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is a wonderful compare and contrast piece. Admittedly I have read little of Thoreau, partly due to my lack of interest in his writing compared to Burroughs, who I find truly genuine, the same for Muir. Thoreau seems bitter and not fully immersed in nature, unwilling to put himself at risk as Muir and Burroughs. Thoreau’s writing is more eloquent and socially driven, and probably more profitable. I like Thoreau’s questioning of people’s motives and prodding to think beyond social norms.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that is a fault of modernity; if a hero has one fault, the entirety of his being is a lie. The is so little ability in our fast pop culture to perceive subtleties. This is why most of my thought life is meditating on forgiveness; it’s the antidote and maybe the salve we need to allow each other to be human.

LikeLike

I agree. It’s easy to be mean. Takes more effort to be understanding. Gotta remund myself of this all the time Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

I tend to agree with your view on HDT. A student recently gave me a copy of Schulz’ acerbic article. I appreciated it for balance. . .yet, as you say, these critiques have been tossed at ol’ Henry for a long time. To me, they don’t stick, much. Yet, again, like all of us who “choose another path” (heretics), we’d do well to expect the pushback!

LikeLike

Thanks Chris, and a good point, if there’s no pushback, you would be by definition going with the flow.

LikeLike

[…] Ancient Greece. These warnings were repeated by 19th-century American Transcendentalists, like Henry David Thoreau and his mentor, Ralph Waldo Emerson, who worried that modern people have lost […]

LikeLike

[…] on the paths. Sometimes I’m reminded of people like John Burroughs, John Muir, and Henry David Thoreau, who wandered the forests during the 19th and early 20th century, experiencing nature as a source […]

LikeLike

[…] I was recently reading the 19th century American Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, interested in their ideas about nature and self-reliance. To my surprise, I discovered they […]

LikeLike

[…] someone who enjoys running in the mountains, I find myself drawn to Henry David Thoreau’s vision of nature and wildness. But when you follow in Thoreau’s path, you discover that his admirers include not […]

LikeLike

[…] encountered Burroughs again when researching Thoreau. Writing in 1882, Burroughs was dismissive of Thoreau as a naturalist and like others recoiled […]

LikeLike

[…] doubt grit plays a role in success, but sensitivity is an important quality, too. Consider Henry David Thoreau, a man whose “life showed a devotion to principle such as one life in millions does not […]

LikeLike

[…] concerns were raised by the American Transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, as well as by John Muir. These writers valued individuality and wildness. They criticized […]

LikeLike