As I dragged myself out of bed, the main topic on my mind was breakfast — not another bushwhacking adventure in the Catskills.

The day before, my friend Todd Jennings and I had put on the inaugural Ellenville Mountain Running Festival. Organizing the race and ensuring everything went smoothly had taken a lot of effort. That night I went to bed tired and didn’t bother to set the alarm. But once I was finally awake and suitably nourished, there were no other pressing tasks at hand, and in due course I found myself motoring down the Thruway in search of Bearpen Mountain.

Todd and I had designed the Ellenville Mountain Running Festival as a “minimalist format” event, meaning that the course wasn’t marked and runners had to carry maps. Many of the racers missed turns and ran extra miles, and a small number gave up and returned to the start. It was only fitting, therefore, that on the way to Bearpen I would get lost. And this despite having both Google Maps and NY-NJ Trail Conference maps on my phone. It was high noon before I pulled into the parking area, almost two hours later than expected. As they say, Karma’s a bitch.

Determined to make up for lost time, I whipped out the trekking poles and launched myself up a steep dirt road. After a few steps, I noticed deer flies, and after a quarter mile, they began to bite. I beat a hasty retreat, retrieved a can of repellent from the car, and sprayed myself thoroughly. And then started out once again.

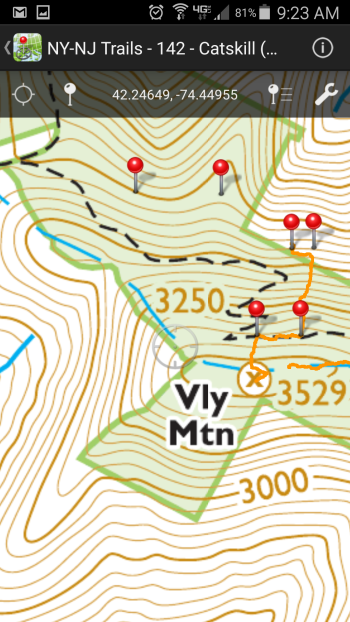

This time I made it to the saddle between Bearpen Mountain and the neighboring peak, Vly Mountain, with the deer flies maintaining a respectful distance. But given the time, I decided to skip Bearpen and climb Vly instead. I was looking for an unmaintained trail that would take me close to Vly’s summit, and sure enough, I stumbled upon a beautiful dirt road pointing in the right direction and trotted happily along toward the mountain. But when I glanced at the Trail Conference map displayed on my phone (picture below), it became apparent this wasn’t the right way. I dropped a couple of waypoints (indicated by red pins on the map) and these showed that the road wasn’t the unmaintained trail indicated on the map, rather it ran north and downhill of the summit.

Out came the compass, and I turned due south, aiming for a bend in the unmaintained trail that passed near the summit. This I missed (my track is indicated by the orange line in the picture), and instead I labored straight uphill toward the summit. It was steep and slow-going, and the footing, unsteady. On a positive note, as a test I was wearing karate-style shinguards to protect my legs from the hobblebush and beech branches that sprawled in great tangles on the slope. They really helped. Nonetheless, the pace was frustratingly slow.

Eventually I reached the unmaintained trail, which was so heavily overgrown as to be virtually unrecognizable. I followed it for a short distance and then turned back into the forest to bushwhack my way to the summit. I then proceeded to spend the better part of an hour searching for the Catskills 3500 Club canister, which is where club members sign in to document a successful ascent. I never found the canister, but I did discover plenty of raspberry canes, whose thorns managed to snag my unprotected knees.

From the berry-infested summit of Vly, I turned east, looking for a route through the woods that would take me down into the next valley. I found an unmarked trail in surprisingly good condition and headed downhill, watching my position carefully on the map, and at the same time taking in the sights and sounds of a beautiful summer afternoon. These included an occasional gunshot echoeing in the distance. Out in the country, people take target practice, firing at cans and the like. It’s called “plinking.” It’s an innocent enough activity, but one doesn’t want to get too close.

The trail disappeared, and then a different one took its place. This new trail hadn’t seen much use in recent years, and while the footing was still flat and firm, there were spots were saplings had sprouted in dense thickets and were growing above my head. Even so, it was faster than following an azimuth straight through the woods, and I made good time down the mountain. The gunfire became somewhat louder.

I was looking for what appeared on the map to be a public road. However, it turned out to be knee-high in grass and wildflowers. I trotted along, and now the gunshots were booming in the next field over. Up ahead there was a locked gate. Had I wandered onto private property? Through a low hedge I heard voices, saw a red barn and a pair of ATVs. A dog began barking. Another shot rang out. I ran through the grass as inconspicuously as possible, ducked around the side of the gate, and finally reached a paved road. I tried to act nonchalant, as if I had been walking along the paved road the whole time.

No-one pursued me, and a quarter mile later, I paused to admire a panoramic vista across meadows, the valley of the West Kill creek, and a line of distant mountains. Later when I looked at the map, I found that the Shandaken Tunnel ran almost under my feet here (part of the water supply system, this tunnel carries up to 600 million gallons a day from the Gilboa Reservoir in Schoharie County to the Esopus Creek, whence it flows into the Ashokan Reservoir and eventually the drinking fountains and faucets of NYC). About three miles to the southeast was a small peak called Balsam Mountain, under which the tunnel lay buried some 2,000 feet. The location of this mountain had been a great mystery to me on a previous visit to the Catskills, and now here it was staring me in the face.

To get back to the car, I took an unnamed trail back up and over the ridge. Along the way, I noticed a distinctive plant with wide, strongly serrated, and prominently veined leaves and clusters of pale flowers. Then I noticed a burning sensation on my unprotected knees and then an elbow, and then on my thigh. Indeed, these plants were Urtica Dioica also known as “Stinging Nettles” or “Burn Weed.” The leaves and stems contain tiny needles that inject a brew of toxins into the unsuspecting passerby, and these toxins impart the stinging, burning sensation. No big deal, after ten or fifteen minutes the irritation would fade. But the farther up the trail, the taller these plants grew, and the more closely they crowded in from the sides, and soon they were sprouting in the middle of the path. It appeared I would have to run a painful gauntlet. I stepped forward carefully and used my trekking poles to prod the offensive plants out of the way.

Eventually the trail ended at a paved road. It was a relief to be done with the nettles! Within a mile or two of the car now, I ran slowly along. I saw an abandoned farmhouse in an advanced stage of decay, with wasp nets nestled in gaps in the walls, but a tractor parked nearby that evidently was still in use. A half a mile down the road there was a much more prosperous farm with extensive fields, all neatly mowed. Then I passed a strange collection of buildings, some of which seemed to be functioning warehouses with trucks parked by their side, while others were dilapidated and surrounded by piles of mechanical equipment which had been left out to rust among the weeds.

I recalled a comment by John Burroughs, the naturalist and writer who had lived in the Catskills in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

These mountains we behold and cross are not picturesque,—they are wild and inhuman as the sea. In them you are in a maze, in a weltering world of woods; you can see neither the earth nor the sky, but a confusion of the growth and decay of centuries.

— John Burroughs, In the Catskills

Indeed, even today “a confusion of growth and decay” seems to be one of the defining characteristics of the Catskills, whether it is in the natural state of the tangled forests, the unmarked trails and old footpaths that are gradually fading away, or the strange collection of structures that humans have built and in some cases abandoned.

Heading back to the car now, I passed a cemetery with polished headstones laid out in neat rows. The late afternoon sun was slanting in, while a breeze stirred the trees. A sign indicated that Walter Scudder was buried here and identified him as one of the ringleaders of the Anti-Rent Movement of the mid-19th century, a period of time when poor tenant farmers protested against collection of back rents owed to their landlords. Disguised in masks and smocks, these protesters came to be known as “Calico Indians,” and they’d band together to intimidate landlords and officers of the law who were attempting to seize land, livestock, and property from delinquent farmers, occasionally treating unpopular landlords to a tarring and feathering, and frequently shooting livestock that had been seized before it could be auctioned.

On August 7, 1845, a brash and unpopular undersheriff named Osman “Bub” Steele attempted to seize and auction a herd of cattle from a delinquent farmer. A band of Anti-Rent Indians confronted him. It’s not clear what happened next, but shots rang out, and Steele fell to the ground, mortally wounded. The Calico Indians realized that things had gone too far; they fled, burned their masks and smocks, and went into hiding. The law responded harshly. John Burroughs remembers watching in fear as heavily armed posses thundered down the roads in search of miscreants to round up.

Five hours after starting out, I was back at the car. Despite the late start, my mission was a success: I’d reached the summit of Vly, discovered a route to the next valley, and learned a little bit of Catskills history. I had braved flies, thorns, gunfire and stinging nettles and emerged unscathed. Except for my knees. The shinguards had worked beautifully, as far as my shins were concerned, but I’d need to do something for my knees next time out. Bermuda Shorts?

[…] tunnel in the woodline opened up. This was a shortcut to the summit which I had taken the last time here. I had marked this point on my Trail Conference map app, indicating the shortcut could be found […]

LikeLike