The acclaimed Japanese animated filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki’s 1988 classic My Neighbor Totoro tells the story of two young sisters who encounter friendly forest spirits in postwar rural Japan. The film has won numerous awards, and the Totoro has been ranked among the most popular animated characters.

There are many reasons for the film’s success, including the carefully crafted animation, the endearing portrayal of the two sisters, the lush watercolor backgrounds, and the pastoral simplicity of the setting. After watching the movie recently, I asked myself, what is a Totoro? And what was Miyazaki’s purpose in creating this movie?

If you haven’t seen the film, its story is set in the countryside outside Tokyo during an unspecified time in the 1950s. In the opening scene, a father and his two daughters are moving from the city to an old house in the country in order to be closer to the mother, who is recovering from tuberculosis in a nearby hospital.

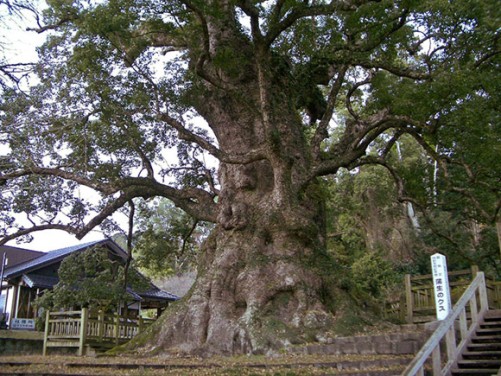

The action begins the next day, when 4-year old Mei is busily exploring the fields surrounding her new home. Miyazaki describes her as a “bold, happy girl,” whose world has not yet been “tainted by the common sense of adults.” Mei spies an acorn glistening in the grass, discovers a trail of them, stumbles upon two small, mysterious creatures — and promptly gives chase. The creatures flee through a dense thicket to the base of a giant camphor tree and disappear beneath its roots.

Hot on their heels, Mei is searching among the tree’s roots when she stumbles into a hole and tumbles down a long tunnel, landing in a mossy cavern beneath the tree. Fast asleep inside this cavern is gigantic, shaggy creature. It wakes up to find a small human has crawled onto its stomach and is tickling its nose. Mei asks if it is a “Totoro” — a mispronunciation of the Japanese word tororu for”troll” — to which it seems to reply in the affirmative. And then goes back to sleep. Enchanted by her new-found friend, Mei drifts asleep astride its furry chest.

Hours later, her older sister Satsuki discovers Mei sleeping alone in the forest. Mei tries to explain what she’s seen and then attempts to lead her family to the cavern under the tree, but can’t find the way back. Her father counsels her that you can only see forest spirits when they want you to.

The next encounter takes place at the neighborhood bust stop. Mei and Satsuki are waiting for their father to return home from work, but the bus is late. It’s raining steadily, and soon it’s dark. Mei is falling asleep on her feet, so Satsuki hoists the little girl onto her back — when footsteps approach. Glancing up, she sees the large Totoro standing next to her in the rain. Her eyes widen in surprise: now she understands what Mei was trying to explain.

Noticing that the Totoro has only a leaf on its head for protection against the rain, Satsuki offers it her father’s umbrella and explains how to use it. The Totoro seems greatly pleased by the sound that raindrops make on the umbrella’s taught fabric. Suddenly a very strange-looking bus appears and skids to a stop– it’s shaped like a cat but has twelve legs. A door opens, and the Totoro steps in — but before departing, hands the startled girls a small package wrapped in a folded leaf. The cat bus takes off, yowling and screeching, and a few moments later, the regular bus arrives and the father steps off.

Back at home, the girls open the package and discover a handful of acorns, which they plant in the garden and dutifully tend, but to Mei’s great frustration, nothing grows. Waking up late one night, they spot the large Totoro and its two small companions dancing in the garden. The girls sneak out of the house and join the dance, and now the acorns sprout and within seconds grow into a massive, magnificent tree. The Totoro pulls out a magic top and gives it a spin, and hopping onto it flies off into the night sky, roaring exuberantly, with the girls and the small Totoros along for the ride. The scene closes with the group sitting on a branch high in the tree, playing ancient flute-like wind instruments (ocarinas) under the full moon.

In the morning, the tree is gone, but the acorns have hatched into seedlings.

The movie is very different from typical Hollywood features. There’s no antagonist in My Neighbor Totoro, no parent-child conflicts, and not much plot. The main drama occurs towards the end of the movie, when the two girls become worried about their mother’s prognosis. Mei sets off by herself, determined to walk all the way to the hospital carrying an ear of corn, which she’s convinced will be good for her mother’s health. When she’s discovered missing, a frantic search ensues, and the tension rises when a child’s sandal is discovered floating in a pond. After running up and down the country roads searching in vain for her little sister, Satsuki rushes to the great camphor tree and implores the Totoros for help. The large one ascends to the top of the tree and summons the cat bus with a roar. The cat bus arrives and opens its door for Satsuki and within seconds they have located Mei. The cat bus then takes the two girls to the hospital, where they see their mother is fine.

In the closing credits, the family is shown happily reunited, while the Totoros continue gathering acorns and tending to the forest. It’s implied that the children will never see these forest spirits again.

Film critic Roger Ebert gave My Neighbor Totoro a four-star rating and added it to his list of the world’s “Great Movies.” As he explained in his review:

It is a little sad, a little scary, a little surprising and a little informative, just like life itself. It depends on a situation instead of a plot, and suggests that the wonder of life and the resources of imagination supply all the adventure you need.

What is a Totoro?

The Totoros, as well as the cat bus, are creations of Miyazaki’s imagination. As he explains in an interview, they play a very specific role in the film: “Because of Totoro’s existence, Satsuki and Mei aren’t isolated and helpless.” Totoro accomplishes this by embodying the spirit of nature and growth and by sharing the feelings of wild exhilaration and quiet contentment.

Interviewers often ask for more detail on the origins of this imaginary creature. Sometimes Miyazaki refers to Totoros using a Japanese word translated as “goblins,” although he clarifies that they have an “easygoing, carefree” attitude and don’t try to frighten people. Sometimes he denies they’re spirits and insists they’re “animals,” pointing out the resemblance to owls, cats, badgers, or bears. Either way, Totoros are “lords of the forest” who can hear “the joyous voices of the plants.” Evidently they live for thousands of years and are invisible to humans — except for children, like Mei and Satsuki, “who notice little things, like acorns, and see the blueness of the sky.”

When pressed further on the Totoro’s origin, Miyzaki states “it would be more accurate to consider him a creature that modern Japanese had to make up out of desperation.”

Desperation at what?

Reading interviews and watching his other films, it’s apparent that Miyazaki harbors concerns about the modern human condition, especially the anger, violence, pollution, and ecological destruction that plague our world. He worries that for many people, there’s no longer much point in putting real effort into work, because “in modern society, humans have become slaves to machines.” He ponders how people are supposed to adapt to life in a high-tech world and reaches no easy conclusion:

When people surrounded by paved roads wonder how they should live, I don’t think there is a markedly new way to live. There is only the classic way we have always lived.

— Hayao Miyazaki

The “classic way” he’s referring to is life in a natural setting. “Everything we value comes from the natural world,” he explains, “we can’t afford to be cut off from the Earth.” Even today, when the Japanese spend little time in natural settings, Miyazaki argues that people still long for the mountains and forests. “The forest represents the origins of humanity,” Miyazaki explains: “We are all born from the forest.”

Even though we have become a modern people, we still feel there is a place where, if we go deep into the mountains, we can find a forest full of beautiful greenery and pure running water that is like a dreamscape.

— Hayao Miyazaki

These feelings arise from deep sources. The Japanese feel a “sense of dark awe” or a feeling of “veneration” towards the forest, Miyazaki states, and he describes his own emotions in this light: “The deep forest is connected in some way to the darkness deep in my heart. I feel that if it is erased, then the darkness inside my heart would also disappear, and my existence would grow shallow.” This is not how a “modern person” feels, he admits, rather it is something “I inherited from far, far in the past.”

Yet for many Japanese people, there’s no longer much connection with the natural world. The primeval broadleaf evergreen forests that once covered the island have been largely replaced by cultivated rural and built-up metropolitan landscapes. Hence the “desperate” need for an animated forest spirit to help people rediscover their connections with nature.

Parallels with Shinto

Shinto is the indigenous, animistic, spiritual tradition of Japan. Unlike Buddhism, Confucianism, or Christianity, Shinto is not an organized religion: there is no founder of Shinto, no official sacred text, and no centralized religious bureaucracy. Yet almost 80% of the population practices Shinto in one form or another, typically through worship and festivals at local shrines, of which there are approximately 80,000 in the country.

The shrines are sacred spaces that house or act as conduits for the kami, a term which is translated variously as “gods,” “spirits,” or “energy” and which can refer to any natural phenomenon that inspires a sense of wonder or awe in the beholder. As explained by Sokyo Ono, professor of Kokugakuin University and an expert on Shinto, shrines are located near “some special tree, grove, rock, cave, mountain, river, or the seashore,” and in rural communities, it may be the case that “shrines are so completely concealed in dense groves or forests that only the local residents are aware of their existence.”

Professor Ono describes the sense of awe or wonder associated with Shinto shrines: “There is a tingle of excitement, a thrill of joy as one enters into a grove which surrounds a shrine.” He elaborates:

Shrine worship is closely associated with a keen sense of the beautiful,— a mystic sense of nature which plays an important part in leading the mind of man from the mundane to the higher and deeper world of the divine…No amount of artificial beauty is an adequate substitute for the beauty of nature.

Sokyo Ono, Shinto the Kami Way

Motohisa Yamakage, a Shinto grand master, make a similar point about the connection between beauty, mysticism, and nature, and he echoes Ono’s and Miyazaki’s concerns about the artificial quality of modern life:

Shinto originally arose from a sense of gratitude and awe toward great nature. Our ancestors loved nature, from animals and plants to mountains and rivers. This love of nature is intrinsic to the Japanese character, influencing our art forms as well as our spiritual practices, even in a modern, urbanized nation where millions of people have little apparent contact with nature.

Motohisa Yamakage, The Essence of Shinto: Japan’s Spiritual Heart

Miyazaki’s love of the forests is completely consistent with Shinto, in which tree worship is a common activity, according to professor Ono. Yamakage explains, “For more than three thousand years, the Japanese have believed that Kami, the powers of the spiritual dimension, can make contact with human beings through trees.” The giant camphor tree in My Neighbor Totoro is identified as a Shinto shrine by the plaited straw cord (shinemawa) that encircles the trunk and by the wooden gate (torii) at the base of the path. Thus you could interpret Totoro as a modern interpretation of kami, designed for an audience that has a greater connection with cinematographic media than with the natural world.

In interviews, Miyazaki avoids mentioning Shinto by name, perhaps because he doesn’t want to get entangled in religious debates. But he admits “I do like animism. I can understand the idea of ascribing character to stones or wind.”

Which is a fair comment from a master animator, who breathes life into still images, creating stories and characters, like the Totoro, that may help people rediscover lost connections.

Having announced his retirement from the film industry, Miyazaki is currently working on a project to create a 10,000 square-meter forested nature preserve to be called “The Forest Where the Wind Returns,” which is designed to encourage children to experience and explore the natural world.

Running the Long Path is available on Amazon (Click on the image to check it out)

[…] on these quotations, we could describe Muir as an animist, i.e., someone who attributes life and spiritual qualities to plants, animals, rocks, and other […]

LikeLike

Totoro is the best character of Ghibli Studio, lots of meaning 🙂

LikeLike

[…] to encounter a bus at the top of the mountain than if we’d chanced upon the Cat-Bus from My Neighbor Totoro. Yet sitting at rest in this sunny clearing full of flowers, the bus looked peaceful, as if this […]

LikeLike

[…] What’s a Totoro? https://medium.com/@niarastorm/what-is-a-totoro-for-one-of-japans-most-iconic-characters-its-nature-is-rather-mysterious-2fb6fde72c41 https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/564973/my-neighbor-totoro-hayao-miyazaki-studio-ghibli-facts […]

LikeLike

[…] What’s a Totoro? https://medium.com/@niarastorm/what-is-a-totoro-for-one-of-japans-most-iconic-characters-its-nature-is-rather-mysterious-2fb6fde72c41 https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/564973/my-neighbor-totoro-hayao-miyazaki-studio-ghibli-facts […]

LikeLike

[…] What’s a Totoro? https://medium.com/@niarastorm/what-is-a-totoro-for-one-of-japans-most-iconic-characters-its-nature-is-rather-mysterious-2fb6fde72c41 https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/564973/my-neighbor-totoro-hayao-miyazaki-studio-ghibli-facts […]

LikeLike

[…] What’s a Totoro? https://medium.com/@niarastorm/what-is-a-totoro-for-one-of-japans-most-iconic-characters-its-nature-is-rather-mysterious-2fb6fde72c41 https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/564973/my-neighbor-totoro-hayao-miyazaki-studio-ghibli-facts […]

LikeLike

[…] What’s a Totoro? https://medium.com/@niarastorm/what-is-a-totoro-for-one-of-japans-most-iconic-characters-its-nature-is-rather-mysterious-2fb6fde72c41 https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/564973/my-neighbor-totoro-hayao-miyazaki-studio-ghibli-facts […]

LikeLike